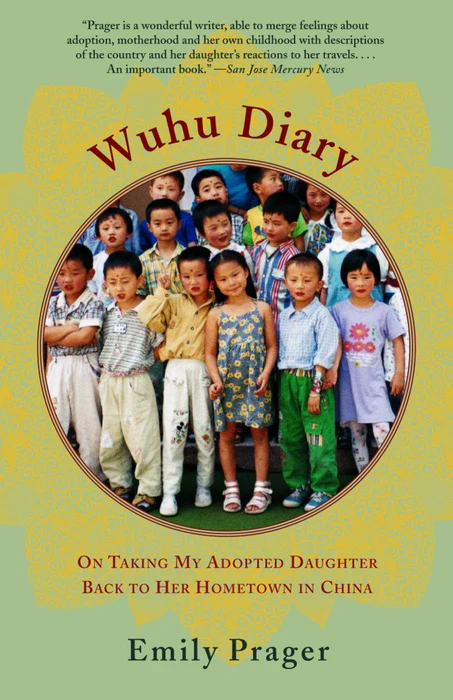

Wuhu Diary

by Anchor

Sold out

Original price

$13.00

-

Original price

$13.00

Original price

$13.00

$13.00

-

$13.00

Current price

$13.00

In 1994 an American writer named Emily Prager met her new daughter LuLu. All she knew about her was that the baby had been born in Wuhu, a city in southern China, and left near a police station in her first three days of life. Her birth mother had left a note with Lulu's western and lunar birth dates. In 1999 Emily and her daughter–now a happy, fearless four-year-old--returned to China to find out more. That journey and its discoveries unfold in this lovely, touching and sensitively observed book.

In Wuhu Diary, we follow Emily and LuLu through a country where children are doted on yet often summarily abandoned and where immense human friendliness can coexist with outbursts of state-orchestrated hostility–particularly after the U. S. accidentally bombs the Chinese embassy in Belgrade. We see Emily unearthing precious details of her child’s past and LuLu coming to terms with who she is. The result is a book that will delight anyone interested in China, and that will move and instruct anyone who has ever adopted--or considered adopting--a child."Prager is a wonderful writer, able to merge feelings about adoption, motherhood and her own childhood with descriptions of the country and her daughter's reactions to her travels. . . . An important book." --San Jose Mercury News

"Moving. . . . For anyone considering multicultural adoption . . . this compelling work offers encouragement and an example of how to help an adopted child get acquainted with her roots and her sense of self. For others it provides a wonderful view of a part of China seldom written about."--Library Journal

“An intimate, everyday portraitÉ.an elegant sense of place, an emotive story of great vulnerability, and a wonderful gift from mother to daughter.” —Kirkus Reviews

“Highly personal. . . . Filled with fascinating information. . . . A welcome addition to the growing literature on adoption.” —BookPageEmily Prager is the author of three novels, Clea & Zeus Divorce, Eve's Tattoo, and the recently published Roger Fishbite, as well as the acclaimed book of short stories A Visit from the Footbinder, and a compendium of her humorous writings, In the Missionary Positions. She has been a satirical columnist for The Village Voice, The New York Observer, and The New York Times, as well as London's Daily Telegraph and The Guardian. She is a Literary Lion of the New York Public Library, and in 2000 she won the first Online Journalism Award for Commentary given by the Columbia University Graduate School of Jounalism. Her books have been published in England, France, Germany, Sweden, Lithuania, and Israel. She teaches humor writing at New York University, and lives in Greenwich Village.Chapter 1

April 30, 1999

Narita Airport, Tokyo

We are close to China now and I can feel it. China, guardian of my memories, nurturer of my spirit. This time, I am taking LuLu, my Chinese daughter, there and I am so excited I can hardly breathe. Going to China always affects me this way. Even though I spent my childhood in Taiwan, China is China to me no matter who rules it. It is a matter of people, trees, birds, smells, and earth, not politics.

This is a "roots" trip for LuLu. I am taking her back to her hometown of Wuhu, in the province of Anhui in southern China. I adopted her on December 12, 1994, at the Anhui Hotel in the provincial capital city of Hefei. She was seven months old then; now she is almost five. She is my daughter now and I am her mother, but then we were just starting out.

It will be a first for me, too, for I have never seen Wuhu, though I am connected to it now by bonds almost as strong as hers.

Somewhere in that city I have never seen, my child was born and put out on the street in her first three days of life. It was near a police station. The police took her in and brought her to the local orphanage, where she was assigned to me, a single woman writer living in Greenwich Village on the other side of the earth. That's basically all we know, what is on her documents. That and what her mother wrote in her note:

This is a girl. Her Western birthday is June 8. Her lunar birthday is April 29, nighttime, at the hour of 11:30 p.m.p.m.

The birth date was computed according to both Chinese and Western calendars. Perhaps her first mother hoped she would be adopted to the West.

I consider this note in her first mother's handwriting to be almost magical. It is Lu's and my only link to the people who created her, that and the genes she carries. We know they were musical. They were expansive. They had great, strong voices, lovely long legs, and remarkable hands. They were eternally cheerful, smart, and good-looking. They had wills of iron and were awfully good-hearted.

It must have been so wrenching for them to leave her. I thought I knew this when I went to China to get her, but it wasn't until I opened the hotel room door and saw her that I truly understood.

I have to confess: I hadn't liked the tiny, two-inch-square photo of her that the adoption ministry sent me after they approved my documents and assigned her to me. She looked kind of thuggish in the picture, and I didn't take to it. But it made me understand that what I was doing was not a fantasy, that I had to be ready to love whatever person came my way, that that was the contract I was making. And I made peace with the photo and carried it proudly in my wallet.

The adoption was arranged through the Spence-Chapin adoption agency. It was like this: after a great deal of paperwork, a group of people-nine couples and two other single women besides myself-came from America together to a hotel in Hefei to embark on the most important journey of our lives. The day we arrived, I was in my room waiting. The babies were meant to come at two. It was noon.

The phone rang. Xion Yan, the Chinese woman who had facilitated the adoptions in China, said joyously, "Would you like to meet your baby?" What a question. I was so thrilled, I could hardly move.

"Oh, yes," I gasped, and put the phone down.

I wasn't ready. I didn't have formula made. I hadn't even read the instructions on the can yet to learn how to do it. I had taken a three-hour course in infant care at Southampton Hospital in Long Island, and that was all I knew about babies. I ran around the room aimlessly, frantically, trying not to have a heart attack, laughing, jumping. Out in the hall I heard baby sounds and then there was a knock at the door.

I'm sure you will understand that opening that door was the most incredible experience. I was about to meet the person I would be responsible for for the rest of my life. I was about to have a baby. I took a deep breath and, as I am wont to do, I plunged in and quickly opened the door.

Which brings me back to the heart-wrenching deed of my in-law (as I think of her), who gave birth to LuLu. Because there before me was a truly lovely-looking baby girl, nothing like the picture, flawless, with red, red cheeks, staring at me with black, sparkling, mischievous eyes.

Her nurse, an older woman, raised the tiny creature up by her shoulders and bent her over in a little bow, whereupon LuLu-for that was the name she came with-broke into the most adorable, grand smile of hello at me. We fell instantly in love and have remained so ever since.

When I examined my child later, I felt a spasm of anguish for the woman who had had to leave her. Did it hurt her forever or did she put the baby down and never look back? I will probably never know.

And I will probably never know what made her do it. It could have been terrible poverty or conception out of wedlock that led her first mother to seal Lu's fate, or it could have been China's one-child policy.

In 1994, the governmental population decree of the People's Republic of China was still stringently enforced. Couples were allowed one child in the city, two in the country. LuLu and the girls in her group were quite probably second children, born to farming families who already had one girl and were hoping for a boy. Secondness, evidently, accounted for their physical strength as well as their destiny.

This is one of the reasons we are going to Wuhu: to see if there is anything in her orphanage file that we do not know; to see what shreds we can gather about LuLu's beginnings. It has been only four years. Perhaps someone remembers something.

When we approach the Narita lounge for the connecting flight to China, everyone waiting there is Chinese. Most are men, and suddenly they all look up, almost as one, and stare at us. I quickly bend down and advise LuLu that in China, large groups of people do have this tendency to gather and stare and it is merely curiosity, in reply to which we should smile.

I flash back to a street in Taipei in 1959. My friend Robin and I are waiting for a car to take us to the Grand Hotel swimming pool. We are both seven, daughters of U.S. Air Force and Army officers. She has flame-red hair. A large crowd of Chinese people has gathered around and stands staring at us, silent and expressionless. We hate it when this happens, because we don't know what these adults want. Robin shouts heatedly at the crowd, which embarrasses me.

In 1979, when my boyfriend and I journeyed to Beijing, a huge crowd followed us everywhere we went. We were among the youngest visitors to the newly opened republic and people were fascinated by us. We were in our early twenties.

But it's not as if the Caucasian mother and Chinese child aren't used to being stared at. On the New York subway or in the supermarket, we are oddities or celebrities, depending on the day.

LuLu has been staring back at those staring at her. She turns to me and grins. "I don't see my world, Mom," she says, and she scampers off into the midst of her countrymen and soon finds a kind Chinese man in his forties who will play with her.

Her world, as she calls it, is the white, urban, middle-class world of New York City, America. There are Asians, Arabs, African-Americans, and Hispanics in it, to be sure, but for the most part, in her immediate world, in her family, she remains a racial minority.

It is for this reason that I sent her to an all-Chinese, Mandarin-speaking preschool in Chinatown, so that in those early years of evolving identity, at least, I would be in the minority someplace, not always she.

And I was. For the first two years, I was the only non-Chinese parent in the school, until others who had adopted or intermarried began to come. And in the beginning, until we were all used to one another, and in spite of my love for China and the Chinese, I always felt, all the time, just a little bit embarrassed, just a little bit self-conscious.

The Red Apple School taught LuLu to be proud of being Chinese and then some, which is exactly what I had hoped they would do. I don't think I could have taught her that. I could teach her to be proud of herself, of being female, of being an American, but pride in one's race is taught, I think, by seeing those of your race do things to be proud of.

LuLu had a lot of great role models at Red Apple. There was the headmistress, Joanna Fan, a dynamic young woman in her thirties who had four preschools and a son, and never stopped cheerfully working. I used to tell her she was building an empire, and she would laugh happily. The last time we saw her, she was building a new preschool in Shanghai and was pregnant with twins.

And, of course, there was Lulu's first teacher, Miss Ling, one of the greatest teachers I have ever seen at work. In Shanghai, Miss Ling had taught classes of thirty-six children under the age of three all by herself. She knew her oats. To watch her teach her class of eighteen toddlers was to see an orchestration in symphonic movements and rhythms. In her clear, singsong voice, she sang the day, and when she sensed the slightest lag of interest in her three-year-old band, she changed the tune. She always carried a little tambourine, which she shook for emphasis, rhythm, and to keep order.

Miss Ling was, in addition, totally adorable-looking, in her early twenties, with a perfectly round face that was always laughing and a ponytail that she fastened on one side of her head.

"Children this age like pretty young women," Joanna told me one day in passing, and Miss Ling certainly was one. She always did LuLu's hair after naptime, and to this day, we call the top-of-head-ponytail hairdo that we learned from her the "Ling" tail in her honor.

LuLu loved her deeply. She made LuLu feel so important. The minute we would arrive at school, LuLu would puff out her little chest and strut proudly into the classroom, and boom out in her strong, clear tones, "Good morning, Lao Sher," which means, "Good morning, Teacher." And Miss Ling would boom back, "Good morning, LuLu Prager."

Undoubtedly, LuLu felt in Miss Ling some of the Chinese mother she had lost. When, after two years, Miss Ling announced that she was leaving to get married and move to Maryland, LuLu was devastated. The night I told her about it, she lay on the bed and tossed and turned. The little three-year-old told me she couldn't sleep.

"I don't want her to get married," she said angrily. And then, from the depths of her heart, "Oh, Mom, I'm going to miss her so much."

I held my little daughter close and comforted her as best I could. I was as stunned at the sophistication of her expression as I was at the depths of her pain. I went immediately into an action panic, as I would over the years whenever the anguish of her separation would suddenly surface. What should I do? How could I help? What to say? What not to say?

Fortunately, it was late spring when Miss Ling left. We went off for vacation to the beach and did not come back to school until the fall. I asked Joanna if we could be invited to the wedding, and one day there was an invitation waiting for us at school. We duly went off to a wedding palace in Chinatown, where we watched Miss Ling change into four different beautiful dresses-two cheongsams and two reminiscent of Scarlett O'Hara-and get married to a nice-looking young man she had met through a matchmaker.

It was in the wedding hall, where I was one of two Caucasians, that LuLu turned to me and said, "You're my Choco."

She was referring to a book we read in which Choco, a bird, has lost his mother and tries to find a new one whom he resembles. Eventually he hooks up with Mrs. Bear, who, though certainly different in appearance from him, is warm and loving and makes apple pie.

"You're . . . you're . . ." she continued, searching for the words.

"Not Chinese," I offered. She nodded.

She had articulated this fact only once before, the previous spring. One day she came home and said, "You look like this." She sucked in her cheeks as hard as she could. Then she let them out and added, smiling proudly, "But I have a Chinese face."

I laughed a lot at her depiction of the angularity of Western faces. Actually, when I was young, my face was so round that people called me "Moonface." And once, when I was an actress on a soap opera at age nineteen, the producer sent down a note to the makeup man. It read, "Do something about Emily. She looks Chinese." And that was my first personal encounter with racism.

I remember the Narita Airport transit lounge from 1994, when I went to get LuLu, although it was not so fancy then. It was here that I first saw Martha. She and her husband, Chris, had joined our adoption group on the way to China. They were film people, and wore anoraks and carried big cameras.

I instantly liked Martha and she me. We were glad to see each other across the lounge, familiar, in this place so far from home. We were being so brave and feeling so scared on this of all trips. Like little girls doing something really exciting together, we caught each other's eyes and smiled like suns.

I can see our group so clearly, sitting around this lounge, waiting nervously for the flight to Beijing: Eshel, Bernice, Martha, and to it in my mind I add Elizabeth, whom we would hook up with at the Forbidden City-the women who became my close friends, the women who accompanied me into motherhood. We sat peering in wonder at one another's tiny photographs, some a little blurry, some-like mine-dotted with ballpoint pen. Our baby daughters. Who were they, with their funny outfits and their funny names?

In Wuhu Diary, we follow Emily and LuLu through a country where children are doted on yet often summarily abandoned and where immense human friendliness can coexist with outbursts of state-orchestrated hostility–particularly after the U. S. accidentally bombs the Chinese embassy in Belgrade. We see Emily unearthing precious details of her child’s past and LuLu coming to terms with who she is. The result is a book that will delight anyone interested in China, and that will move and instruct anyone who has ever adopted--or considered adopting--a child."Prager is a wonderful writer, able to merge feelings about adoption, motherhood and her own childhood with descriptions of the country and her daughter's reactions to her travels. . . . An important book." --San Jose Mercury News

"Moving. . . . For anyone considering multicultural adoption . . . this compelling work offers encouragement and an example of how to help an adopted child get acquainted with her roots and her sense of self. For others it provides a wonderful view of a part of China seldom written about."--Library Journal

“An intimate, everyday portraitÉ.an elegant sense of place, an emotive story of great vulnerability, and a wonderful gift from mother to daughter.” —Kirkus Reviews

“Highly personal. . . . Filled with fascinating information. . . . A welcome addition to the growing literature on adoption.” —BookPageEmily Prager is the author of three novels, Clea & Zeus Divorce, Eve's Tattoo, and the recently published Roger Fishbite, as well as the acclaimed book of short stories A Visit from the Footbinder, and a compendium of her humorous writings, In the Missionary Positions. She has been a satirical columnist for The Village Voice, The New York Observer, and The New York Times, as well as London's Daily Telegraph and The Guardian. She is a Literary Lion of the New York Public Library, and in 2000 she won the first Online Journalism Award for Commentary given by the Columbia University Graduate School of Jounalism. Her books have been published in England, France, Germany, Sweden, Lithuania, and Israel. She teaches humor writing at New York University, and lives in Greenwich Village.Chapter 1

April 30, 1999

Narita Airport, Tokyo

We are close to China now and I can feel it. China, guardian of my memories, nurturer of my spirit. This time, I am taking LuLu, my Chinese daughter, there and I am so excited I can hardly breathe. Going to China always affects me this way. Even though I spent my childhood in Taiwan, China is China to me no matter who rules it. It is a matter of people, trees, birds, smells, and earth, not politics.

This is a "roots" trip for LuLu. I am taking her back to her hometown of Wuhu, in the province of Anhui in southern China. I adopted her on December 12, 1994, at the Anhui Hotel in the provincial capital city of Hefei. She was seven months old then; now she is almost five. She is my daughter now and I am her mother, but then we were just starting out.

It will be a first for me, too, for I have never seen Wuhu, though I am connected to it now by bonds almost as strong as hers.

Somewhere in that city I have never seen, my child was born and put out on the street in her first three days of life. It was near a police station. The police took her in and brought her to the local orphanage, where she was assigned to me, a single woman writer living in Greenwich Village on the other side of the earth. That's basically all we know, what is on her documents. That and what her mother wrote in her note:

This is a girl. Her Western birthday is June 8. Her lunar birthday is April 29, nighttime, at the hour of 11:30 p.m.p.m.

The birth date was computed according to both Chinese and Western calendars. Perhaps her first mother hoped she would be adopted to the West.

I consider this note in her first mother's handwriting to be almost magical. It is Lu's and my only link to the people who created her, that and the genes she carries. We know they were musical. They were expansive. They had great, strong voices, lovely long legs, and remarkable hands. They were eternally cheerful, smart, and good-looking. They had wills of iron and were awfully good-hearted.

It must have been so wrenching for them to leave her. I thought I knew this when I went to China to get her, but it wasn't until I opened the hotel room door and saw her that I truly understood.

I have to confess: I hadn't liked the tiny, two-inch-square photo of her that the adoption ministry sent me after they approved my documents and assigned her to me. She looked kind of thuggish in the picture, and I didn't take to it. But it made me understand that what I was doing was not a fantasy, that I had to be ready to love whatever person came my way, that that was the contract I was making. And I made peace with the photo and carried it proudly in my wallet.

The adoption was arranged through the Spence-Chapin adoption agency. It was like this: after a great deal of paperwork, a group of people-nine couples and two other single women besides myself-came from America together to a hotel in Hefei to embark on the most important journey of our lives. The day we arrived, I was in my room waiting. The babies were meant to come at two. It was noon.

The phone rang. Xion Yan, the Chinese woman who had facilitated the adoptions in China, said joyously, "Would you like to meet your baby?" What a question. I was so thrilled, I could hardly move.

"Oh, yes," I gasped, and put the phone down.

I wasn't ready. I didn't have formula made. I hadn't even read the instructions on the can yet to learn how to do it. I had taken a three-hour course in infant care at Southampton Hospital in Long Island, and that was all I knew about babies. I ran around the room aimlessly, frantically, trying not to have a heart attack, laughing, jumping. Out in the hall I heard baby sounds and then there was a knock at the door.

I'm sure you will understand that opening that door was the most incredible experience. I was about to meet the person I would be responsible for for the rest of my life. I was about to have a baby. I took a deep breath and, as I am wont to do, I plunged in and quickly opened the door.

Which brings me back to the heart-wrenching deed of my in-law (as I think of her), who gave birth to LuLu. Because there before me was a truly lovely-looking baby girl, nothing like the picture, flawless, with red, red cheeks, staring at me with black, sparkling, mischievous eyes.

Her nurse, an older woman, raised the tiny creature up by her shoulders and bent her over in a little bow, whereupon LuLu-for that was the name she came with-broke into the most adorable, grand smile of hello at me. We fell instantly in love and have remained so ever since.

When I examined my child later, I felt a spasm of anguish for the woman who had had to leave her. Did it hurt her forever or did she put the baby down and never look back? I will probably never know.

And I will probably never know what made her do it. It could have been terrible poverty or conception out of wedlock that led her first mother to seal Lu's fate, or it could have been China's one-child policy.

In 1994, the governmental population decree of the People's Republic of China was still stringently enforced. Couples were allowed one child in the city, two in the country. LuLu and the girls in her group were quite probably second children, born to farming families who already had one girl and were hoping for a boy. Secondness, evidently, accounted for their physical strength as well as their destiny.

This is one of the reasons we are going to Wuhu: to see if there is anything in her orphanage file that we do not know; to see what shreds we can gather about LuLu's beginnings. It has been only four years. Perhaps someone remembers something.

When we approach the Narita lounge for the connecting flight to China, everyone waiting there is Chinese. Most are men, and suddenly they all look up, almost as one, and stare at us. I quickly bend down and advise LuLu that in China, large groups of people do have this tendency to gather and stare and it is merely curiosity, in reply to which we should smile.

I flash back to a street in Taipei in 1959. My friend Robin and I are waiting for a car to take us to the Grand Hotel swimming pool. We are both seven, daughters of U.S. Air Force and Army officers. She has flame-red hair. A large crowd of Chinese people has gathered around and stands staring at us, silent and expressionless. We hate it when this happens, because we don't know what these adults want. Robin shouts heatedly at the crowd, which embarrasses me.

In 1979, when my boyfriend and I journeyed to Beijing, a huge crowd followed us everywhere we went. We were among the youngest visitors to the newly opened republic and people were fascinated by us. We were in our early twenties.

But it's not as if the Caucasian mother and Chinese child aren't used to being stared at. On the New York subway or in the supermarket, we are oddities or celebrities, depending on the day.

LuLu has been staring back at those staring at her. She turns to me and grins. "I don't see my world, Mom," she says, and she scampers off into the midst of her countrymen and soon finds a kind Chinese man in his forties who will play with her.

Her world, as she calls it, is the white, urban, middle-class world of New York City, America. There are Asians, Arabs, African-Americans, and Hispanics in it, to be sure, but for the most part, in her immediate world, in her family, she remains a racial minority.

It is for this reason that I sent her to an all-Chinese, Mandarin-speaking preschool in Chinatown, so that in those early years of evolving identity, at least, I would be in the minority someplace, not always she.

And I was. For the first two years, I was the only non-Chinese parent in the school, until others who had adopted or intermarried began to come. And in the beginning, until we were all used to one another, and in spite of my love for China and the Chinese, I always felt, all the time, just a little bit embarrassed, just a little bit self-conscious.

The Red Apple School taught LuLu to be proud of being Chinese and then some, which is exactly what I had hoped they would do. I don't think I could have taught her that. I could teach her to be proud of herself, of being female, of being an American, but pride in one's race is taught, I think, by seeing those of your race do things to be proud of.

LuLu had a lot of great role models at Red Apple. There was the headmistress, Joanna Fan, a dynamic young woman in her thirties who had four preschools and a son, and never stopped cheerfully working. I used to tell her she was building an empire, and she would laugh happily. The last time we saw her, she was building a new preschool in Shanghai and was pregnant with twins.

And, of course, there was Lulu's first teacher, Miss Ling, one of the greatest teachers I have ever seen at work. In Shanghai, Miss Ling had taught classes of thirty-six children under the age of three all by herself. She knew her oats. To watch her teach her class of eighteen toddlers was to see an orchestration in symphonic movements and rhythms. In her clear, singsong voice, she sang the day, and when she sensed the slightest lag of interest in her three-year-old band, she changed the tune. She always carried a little tambourine, which she shook for emphasis, rhythm, and to keep order.

Miss Ling was, in addition, totally adorable-looking, in her early twenties, with a perfectly round face that was always laughing and a ponytail that she fastened on one side of her head.

"Children this age like pretty young women," Joanna told me one day in passing, and Miss Ling certainly was one. She always did LuLu's hair after naptime, and to this day, we call the top-of-head-ponytail hairdo that we learned from her the "Ling" tail in her honor.

LuLu loved her deeply. She made LuLu feel so important. The minute we would arrive at school, LuLu would puff out her little chest and strut proudly into the classroom, and boom out in her strong, clear tones, "Good morning, Lao Sher," which means, "Good morning, Teacher." And Miss Ling would boom back, "Good morning, LuLu Prager."

Undoubtedly, LuLu felt in Miss Ling some of the Chinese mother she had lost. When, after two years, Miss Ling announced that she was leaving to get married and move to Maryland, LuLu was devastated. The night I told her about it, she lay on the bed and tossed and turned. The little three-year-old told me she couldn't sleep.

"I don't want her to get married," she said angrily. And then, from the depths of her heart, "Oh, Mom, I'm going to miss her so much."

I held my little daughter close and comforted her as best I could. I was as stunned at the sophistication of her expression as I was at the depths of her pain. I went immediately into an action panic, as I would over the years whenever the anguish of her separation would suddenly surface. What should I do? How could I help? What to say? What not to say?

Fortunately, it was late spring when Miss Ling left. We went off for vacation to the beach and did not come back to school until the fall. I asked Joanna if we could be invited to the wedding, and one day there was an invitation waiting for us at school. We duly went off to a wedding palace in Chinatown, where we watched Miss Ling change into four different beautiful dresses-two cheongsams and two reminiscent of Scarlett O'Hara-and get married to a nice-looking young man she had met through a matchmaker.

It was in the wedding hall, where I was one of two Caucasians, that LuLu turned to me and said, "You're my Choco."

She was referring to a book we read in which Choco, a bird, has lost his mother and tries to find a new one whom he resembles. Eventually he hooks up with Mrs. Bear, who, though certainly different in appearance from him, is warm and loving and makes apple pie.

"You're . . . you're . . ." she continued, searching for the words.

"Not Chinese," I offered. She nodded.

She had articulated this fact only once before, the previous spring. One day she came home and said, "You look like this." She sucked in her cheeks as hard as she could. Then she let them out and added, smiling proudly, "But I have a Chinese face."

I laughed a lot at her depiction of the angularity of Western faces. Actually, when I was young, my face was so round that people called me "Moonface." And once, when I was an actress on a soap opera at age nineteen, the producer sent down a note to the makeup man. It read, "Do something about Emily. She looks Chinese." And that was my first personal encounter with racism.

I remember the Narita Airport transit lounge from 1994, when I went to get LuLu, although it was not so fancy then. It was here that I first saw Martha. She and her husband, Chris, had joined our adoption group on the way to China. They were film people, and wore anoraks and carried big cameras.

I instantly liked Martha and she me. We were glad to see each other across the lounge, familiar, in this place so far from home. We were being so brave and feeling so scared on this of all trips. Like little girls doing something really exciting together, we caught each other's eyes and smiled like suns.

I can see our group so clearly, sitting around this lounge, waiting nervously for the flight to Beijing: Eshel, Bernice, Martha, and to it in my mind I add Elizabeth, whom we would hook up with at the Forbidden City-the women who became my close friends, the women who accompanied me into motherhood. We sat peering in wonder at one another's tiny photographs, some a little blurry, some-like mine-dotted with ballpoint pen. Our baby daughters. Who were they, with their funny outfits and their funny names?

PUBLISHER:

Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group

ISBN-10:

0385721994

ISBN-13:

9780385721998

BINDING:

Paperback

BOOK DIMENSIONS:

Dimensions: 5.2000(W) x Dimensions: 7.9900(H) x Dimensions: 0.6500(D)