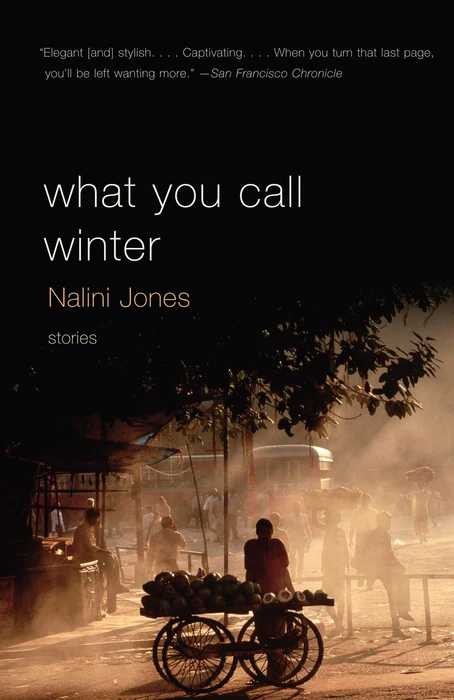

What You Call Winter

by Anchor

Sold out

Original price

$14.95

-

Original price

$14.95

Original price

$14.95

$14.95

-

$14.95

Current price

$14.95

Composed of interconnected stories that move within and around a small Catholic community in India, this debut collection heralds the arrival of a graceful, sparkling new voice.

Nine-year-old Marian Almeida covets the green dress her parents have set aside for her birthday, but when her desire gets the best of her, dangerous events ensue. Roddy D'Souza sees his long-dead father bicycling down the street, and wonders if his own life is nearing its close. Essie, having sent her son to boarding school, weighs his unhappiness against the opportunities his education will provide. With empathy and poise, Nalini Jones creates in What You Call Winter a spellbinding work of families in an uncertain world.“Elegant [and] stylish. . . . Captivating. . . . When you turn that last page, you'll be left wanting more.” —San Francisco Chronicle“Like Chekhov-and this young writer is good enough to merit the comparison-Jones has faith in details. . . . We always sense the organizing intelligence and compassion of an author who invites us to understand rather than to judge.” —The Washington Post Book World“What You Call Winter is a momentous debut, a bewitching exploration of what it means to belong, anywhere.” —Elle“Luminous. . . . Polished . . . [What You Call Winter] shines light on [the world of Indians].” —Entertainment WeeklyNalini Jones was born in Newport, Rhode Island, graduated from Amherst College, and received an M.F.A. from Columbia University. Her work has appeared in the Ontario Review, Glimmer Train, Dogwood, and Creative Nonfiction's "Living Issue." She is a Stanford Calderwood Fellow of the MacDowell Colony, and has recently taught at the 92nd Street Y in New York and Fairfield University in Connecticut.In the GardenThree days before her tenth birthday, Marian Almeida came home unexpectedly early. Usually her afternoons were spent at Uncle Neddie’s, who was no uncle of hers at all but the nearest neighbor with a piano for her practice. Of course, Uncle Neddie and his wife and his three unmusical children spent the drowsy stretch of hours before supper curled on narrow mattresses, napping through the merciless heat. The shops were closed, dogs panted under wiry trees, shadows darkly spotted the roads and yards. The servants sifted rice or ground spices; the dancing grains and elliptical rhythm of mortar and pestle lulled even the restless children to slumber. Marian, seated before the scarred wooden box of Uncle Neddie’s piano, touched her fingers to the yellowed keys so lightly that she did not make a sound. She practiced her fingering in silence while the household slept. “It shouldn’t make a difference, how hard you thump,” her mother had decided when she arranged for Marian’s practice sessions. “You can just learn the shapes of songs for now.” On lesson days, when Marian perched on the glossy black bench of St. Jerome’s piano, the noise of her own playing startled her.But Uncle Neddie’s wife, known to the neighborhood as Aunty Neddie although it was commonly believed that she must once have enjoyed a name of her own, met Marian at the door with the news that one of the children had fallen ill. “Go on, then.” She shooed the girl away. “Tell Mummy not another week, at least. We can’t have you carrying anything home.”Marian imagined carrying the germs of the sick Neddies in her belly. She thought of the careful way she would have to lower herself into chairs. Her own mother, she’d been told, was carrying twins.The afternoon spun before her, golden and dusty, suddenly free. Marian walked home with a mounting sense of excitement. She had two hours, at least, before her mother finished tutoring, perhaps longer if she stopped off to market. (Marian’s daily bouts at the piano lasted ninety minutes, with extra time, her mother reasoned, for imagining the sounds.) Usually, Marian had just enough time to change out of her school uniform skirt before her mother arrived and homework began. Sometimes, if she hurried to reach St. Hilary Road before six, she might run into her father, home from the university but on his way out again to meet his friends at the Santa Clara Gymkhana. Perhaps this was the day she could go with him, she thought. Some of his friends were Parsees, named for their jobs and not for saints like Marian and all the Indian Catholics. Her father’s name was Francis, but the Parsees called him “Frinkie,” which made him laugh in a way he never laughed at home.For a moment Marian thought of her brother, Simon, two years younger and still trapped at his desk, and she felt a pang of sympathy that threatened to spoil her own enjoyment. Twice a week Simon took special classes after school to prepare him for seminary, which both of them agreed was rotten luck. But every second day he was allowed to bowl for the cricket team, she reminded herself. Nobody had ever suggested he take up piano, Marian further realized, and found she could once again rejoice in her good fortune. The road flew beneath her feet in jerks and rushes as she began to skip—past the tall gates of St. Jerome’s Church, where families of beggars held out their hands to the Catholic ladies. One small girl, whose hair was thick and matted, the color of clay, looked sorrowfully as Marian sped by.“Wait, madam!” the child called in English, and Marian, shocked, stopped and turned to face her. Marian and her family and most of the middle-class Catholic families spoke English in their homes, but to many others—insurance salesmen, shopkeepers, servants, taxi drivers—they spoke Hindi or Marathi or some swirl of all three. Beggars almost never spoke English.The small girl glared at her, continuing in Hindi. “You could buy me an ice cream, at least.”“No, I can’t.”The child scowled.“I’m going now,” Marian told her.A boy came to stand beside the girl, jostling her shoulder. “Why do you bother with schoolgirls?” Marian heard him scolding.Her father’s house, squatting in the sun behind a black iron gate, seemed transformed with nobody filling its rooms. Marian couldn’t remember the last time she’d been home alone. Only Togo, napping in a patch of shade at the foot of the porch steps, lifted his head for a moment and whined before dropping to sleep again on the cool tile. Marian had to use her key to open the door at the head of the stairs. Inside, silence settled, thick and swampy, on stacks of books, the radio, the teapot and stained spoons left out from lunch. The hands of the clock drifted slowly toward evening, as if through water. Marian moved quietly in the shadowy green light, checking bedrooms, the kitchen, the back balcony, where washing hung on slack lengths of line. She felt she’d entered a private world, interrupted only by the low whir of fans. Even Martha was gone.Marian’s mother gave all her servants the same Christian name. Several Marthas had come to Bombay from the villages near Mangalore to live with Marian’s family. Easter Almeida, attentive to their equal need for literacy and the Lord, had launched the careers of every girl with the instructive tale of their common namesake, a friend of Jesus’s “cumbered about much serving.” Marian could remember listening to three such beginnings, leaning against the doorframe, twining a strand of hair around her finger. “What are you doing, hanging about?” her mother snapped at her the last time. “You gawk like a hawk.” Thou art troubled about many things, Marian thought, staring at the stout braid of her mother’s hair before she slipped away without a word. The shapes of retorts were enough for Marian. That was nearly two years ago, just after she won St. Jerome’s Sunday school prize for reciting Bible verses.Marian untied the red ribbons from the ends of her braids and peeled herself a sweet lime before she wandered through the living room. Threads of light needled through the woven shades and fell across the tile floor in a golden mesh. She stepped past the print of the Virgin, whose eyes followed her onto the front balcony: a bank of windows over a balustrade with wooden doors that could be closed in the monsoon season. Now they were latched open. Marian hoisted up the shade just enough to see a single bright stripe of lawn below, then higher and higher, revealing the guava tree, the gate, the street gutter, the road. An Ambassador taxi buzzed slowly past like a fat summer fly, and she could hear the lazy calls of crows. She tried to imagine what every member of her family might be doing at that precise instant. Her father, on a train; her mother, in a classroom; her brother, bent over the book on his desk. Martha, sent to market, with just enough coins in her drawstring sack. She glanced again at the road. A stream of bullocks trickled ahead of a boy with a stick. Marian listened to the thin ringing of their bells, broken into pieces by the rise and fall of each bony shoulder, and thought that even the shape of the cattle’s song turned drowsy in the afternoon. Her stomach had begun to ache, and she thought she might curl up on her bunk and read.But she didn’t want to waste her free time sleeping. Instead, she began to rummage through the wardrobe her parents shared. She pushed past the skirts and blouses her mother used for everyday wear and began to run her fingers along the silken folds of her mother’s saris. Most of the Catholic women of Santa Clara wore their good Indian outfits only for church or weddings or parties—and of course to go to the city, a forty-minute ride on the commuter train. The girls wore uniform jumpers to school and frilly dresses or kameez and churidar at parties. Only when Marian was fully grown would she have her own saris and blouses. But she was searching for an old cotton sari, which she had once been permitted to try on.Her mother had had to help her tuck it, nearly doubled at the waist, and three paces across the room the fabric slipped from Marian’s waist and shoulders. You’re too small, her mother had protested, but she had been smiling. Finally Marian tensed the muscles of her arms and legs into marionette stiffness and made it across the length of the living room. Her mother clapped her hands and called her a little rani. Her father bowed and asked for a dance, and Simon clowned about like a footman behind her, lifting a trailing edge of cloth.In three days, Marian would be ten years old. Old enough to help with the babies when they came, her mother told her. Old enough to play the piano in a recital, old enough to listen without talking back, old enough to write letters to Aunty Trudy in Bangalore, who answered them in envelopes addressed to Miss Marian Almeida. Old enough not to fuss when Simon called her Miss Marian, Marian, Quite Contrarian. (Suffer it to be so now, thought Marian, armed with her Bible verses, whenever he annoyed her.) Old enough, she was certain, to put the sari on herself. She would surprise the whole family when they came home. She would set them all laughing. Her mother might let her choose a bindi for her forehead. Simon would lose the pinched face he wore whenever he came home from school. Martha would look on from the kitchen and flash her broad grin, putting one finger over her mouth where a tooth had rotted away. Hushing the shape of her smile. Even Marian’s father would stay home from the gym, and when he’d had his cup of tea, he would find the red cushion and stand on his head. He would stay upside down until all the old stories of when he was a boy came rushing back from wherever they’d been lost. They fell into his feet and couldn’t find his mouth, he used to tell Marian, or they wiggled through his arms to the tips of his fingers, or they hid in his stomach with last night’s fish. “They’ve gone down to my bottom this time,” he exclaimed when her mother was out of the room, and he’d smack the back of his pants to get them moving again. Marian was old enough not to believe him, of course, but still she missed the game. Usually he came home just in time for supper, then spent the evening at his desk, rubbing the back of his neck. Marian used to cover her head with her pillow when her parents argued, but now they fought only in small bites and jabs. She fell asleep most nights, listening to ice cubes in her father’s glass, her mother’s pen scratching across the page. The shapes of shouting, she thought, even in the quiet. She wondered if the twins could hear what her mother was thinking.

Nine-year-old Marian Almeida covets the green dress her parents have set aside for her birthday, but when her desire gets the best of her, dangerous events ensue. Roddy D'Souza sees his long-dead father bicycling down the street, and wonders if his own life is nearing its close. Essie, having sent her son to boarding school, weighs his unhappiness against the opportunities his education will provide. With empathy and poise, Nalini Jones creates in What You Call Winter a spellbinding work of families in an uncertain world.“Elegant [and] stylish. . . . Captivating. . . . When you turn that last page, you'll be left wanting more.” —San Francisco Chronicle“Like Chekhov-and this young writer is good enough to merit the comparison-Jones has faith in details. . . . We always sense the organizing intelligence and compassion of an author who invites us to understand rather than to judge.” —The Washington Post Book World“What You Call Winter is a momentous debut, a bewitching exploration of what it means to belong, anywhere.” —Elle“Luminous. . . . Polished . . . [What You Call Winter] shines light on [the world of Indians].” —Entertainment WeeklyNalini Jones was born in Newport, Rhode Island, graduated from Amherst College, and received an M.F.A. from Columbia University. Her work has appeared in the Ontario Review, Glimmer Train, Dogwood, and Creative Nonfiction's "Living Issue." She is a Stanford Calderwood Fellow of the MacDowell Colony, and has recently taught at the 92nd Street Y in New York and Fairfield University in Connecticut.In the GardenThree days before her tenth birthday, Marian Almeida came home unexpectedly early. Usually her afternoons were spent at Uncle Neddie’s, who was no uncle of hers at all but the nearest neighbor with a piano for her practice. Of course, Uncle Neddie and his wife and his three unmusical children spent the drowsy stretch of hours before supper curled on narrow mattresses, napping through the merciless heat. The shops were closed, dogs panted under wiry trees, shadows darkly spotted the roads and yards. The servants sifted rice or ground spices; the dancing grains and elliptical rhythm of mortar and pestle lulled even the restless children to slumber. Marian, seated before the scarred wooden box of Uncle Neddie’s piano, touched her fingers to the yellowed keys so lightly that she did not make a sound. She practiced her fingering in silence while the household slept. “It shouldn’t make a difference, how hard you thump,” her mother had decided when she arranged for Marian’s practice sessions. “You can just learn the shapes of songs for now.” On lesson days, when Marian perched on the glossy black bench of St. Jerome’s piano, the noise of her own playing startled her.But Uncle Neddie’s wife, known to the neighborhood as Aunty Neddie although it was commonly believed that she must once have enjoyed a name of her own, met Marian at the door with the news that one of the children had fallen ill. “Go on, then.” She shooed the girl away. “Tell Mummy not another week, at least. We can’t have you carrying anything home.”Marian imagined carrying the germs of the sick Neddies in her belly. She thought of the careful way she would have to lower herself into chairs. Her own mother, she’d been told, was carrying twins.The afternoon spun before her, golden and dusty, suddenly free. Marian walked home with a mounting sense of excitement. She had two hours, at least, before her mother finished tutoring, perhaps longer if she stopped off to market. (Marian’s daily bouts at the piano lasted ninety minutes, with extra time, her mother reasoned, for imagining the sounds.) Usually, Marian had just enough time to change out of her school uniform skirt before her mother arrived and homework began. Sometimes, if she hurried to reach St. Hilary Road before six, she might run into her father, home from the university but on his way out again to meet his friends at the Santa Clara Gymkhana. Perhaps this was the day she could go with him, she thought. Some of his friends were Parsees, named for their jobs and not for saints like Marian and all the Indian Catholics. Her father’s name was Francis, but the Parsees called him “Frinkie,” which made him laugh in a way he never laughed at home.For a moment Marian thought of her brother, Simon, two years younger and still trapped at his desk, and she felt a pang of sympathy that threatened to spoil her own enjoyment. Twice a week Simon took special classes after school to prepare him for seminary, which both of them agreed was rotten luck. But every second day he was allowed to bowl for the cricket team, she reminded herself. Nobody had ever suggested he take up piano, Marian further realized, and found she could once again rejoice in her good fortune. The road flew beneath her feet in jerks and rushes as she began to skip—past the tall gates of St. Jerome’s Church, where families of beggars held out their hands to the Catholic ladies. One small girl, whose hair was thick and matted, the color of clay, looked sorrowfully as Marian sped by.“Wait, madam!” the child called in English, and Marian, shocked, stopped and turned to face her. Marian and her family and most of the middle-class Catholic families spoke English in their homes, but to many others—insurance salesmen, shopkeepers, servants, taxi drivers—they spoke Hindi or Marathi or some swirl of all three. Beggars almost never spoke English.The small girl glared at her, continuing in Hindi. “You could buy me an ice cream, at least.”“No, I can’t.”The child scowled.“I’m going now,” Marian told her.A boy came to stand beside the girl, jostling her shoulder. “Why do you bother with schoolgirls?” Marian heard him scolding.Her father’s house, squatting in the sun behind a black iron gate, seemed transformed with nobody filling its rooms. Marian couldn’t remember the last time she’d been home alone. Only Togo, napping in a patch of shade at the foot of the porch steps, lifted his head for a moment and whined before dropping to sleep again on the cool tile. Marian had to use her key to open the door at the head of the stairs. Inside, silence settled, thick and swampy, on stacks of books, the radio, the teapot and stained spoons left out from lunch. The hands of the clock drifted slowly toward evening, as if through water. Marian moved quietly in the shadowy green light, checking bedrooms, the kitchen, the back balcony, where washing hung on slack lengths of line. She felt she’d entered a private world, interrupted only by the low whir of fans. Even Martha was gone.Marian’s mother gave all her servants the same Christian name. Several Marthas had come to Bombay from the villages near Mangalore to live with Marian’s family. Easter Almeida, attentive to their equal need for literacy and the Lord, had launched the careers of every girl with the instructive tale of their common namesake, a friend of Jesus’s “cumbered about much serving.” Marian could remember listening to three such beginnings, leaning against the doorframe, twining a strand of hair around her finger. “What are you doing, hanging about?” her mother snapped at her the last time. “You gawk like a hawk.” Thou art troubled about many things, Marian thought, staring at the stout braid of her mother’s hair before she slipped away without a word. The shapes of retorts were enough for Marian. That was nearly two years ago, just after she won St. Jerome’s Sunday school prize for reciting Bible verses.Marian untied the red ribbons from the ends of her braids and peeled herself a sweet lime before she wandered through the living room. Threads of light needled through the woven shades and fell across the tile floor in a golden mesh. She stepped past the print of the Virgin, whose eyes followed her onto the front balcony: a bank of windows over a balustrade with wooden doors that could be closed in the monsoon season. Now they were latched open. Marian hoisted up the shade just enough to see a single bright stripe of lawn below, then higher and higher, revealing the guava tree, the gate, the street gutter, the road. An Ambassador taxi buzzed slowly past like a fat summer fly, and she could hear the lazy calls of crows. She tried to imagine what every member of her family might be doing at that precise instant. Her father, on a train; her mother, in a classroom; her brother, bent over the book on his desk. Martha, sent to market, with just enough coins in her drawstring sack. She glanced again at the road. A stream of bullocks trickled ahead of a boy with a stick. Marian listened to the thin ringing of their bells, broken into pieces by the rise and fall of each bony shoulder, and thought that even the shape of the cattle’s song turned drowsy in the afternoon. Her stomach had begun to ache, and she thought she might curl up on her bunk and read.But she didn’t want to waste her free time sleeping. Instead, she began to rummage through the wardrobe her parents shared. She pushed past the skirts and blouses her mother used for everyday wear and began to run her fingers along the silken folds of her mother’s saris. Most of the Catholic women of Santa Clara wore their good Indian outfits only for church or weddings or parties—and of course to go to the city, a forty-minute ride on the commuter train. The girls wore uniform jumpers to school and frilly dresses or kameez and churidar at parties. Only when Marian was fully grown would she have her own saris and blouses. But she was searching for an old cotton sari, which she had once been permitted to try on.Her mother had had to help her tuck it, nearly doubled at the waist, and three paces across the room the fabric slipped from Marian’s waist and shoulders. You’re too small, her mother had protested, but she had been smiling. Finally Marian tensed the muscles of her arms and legs into marionette stiffness and made it across the length of the living room. Her mother clapped her hands and called her a little rani. Her father bowed and asked for a dance, and Simon clowned about like a footman behind her, lifting a trailing edge of cloth.In three days, Marian would be ten years old. Old enough to help with the babies when they came, her mother told her. Old enough to play the piano in a recital, old enough to listen without talking back, old enough to write letters to Aunty Trudy in Bangalore, who answered them in envelopes addressed to Miss Marian Almeida. Old enough not to fuss when Simon called her Miss Marian, Marian, Quite Contrarian. (Suffer it to be so now, thought Marian, armed with her Bible verses, whenever he annoyed her.) Old enough, she was certain, to put the sari on herself. She would surprise the whole family when they came home. She would set them all laughing. Her mother might let her choose a bindi for her forehead. Simon would lose the pinched face he wore whenever he came home from school. Martha would look on from the kitchen and flash her broad grin, putting one finger over her mouth where a tooth had rotted away. Hushing the shape of her smile. Even Marian’s father would stay home from the gym, and when he’d had his cup of tea, he would find the red cushion and stand on his head. He would stay upside down until all the old stories of when he was a boy came rushing back from wherever they’d been lost. They fell into his feet and couldn’t find his mouth, he used to tell Marian, or they wiggled through his arms to the tips of his fingers, or they hid in his stomach with last night’s fish. “They’ve gone down to my bottom this time,” he exclaimed when her mother was out of the room, and he’d smack the back of his pants to get them moving again. Marian was old enough not to believe him, of course, but still she missed the game. Usually he came home just in time for supper, then spent the evening at his desk, rubbing the back of his neck. Marian used to cover her head with her pillow when her parents argued, but now they fought only in small bites and jabs. She fell asleep most nights, listening to ice cubes in her father’s glass, her mother’s pen scratching across the page. The shapes of shouting, she thought, even in the quiet. She wondered if the twins could hear what her mother was thinking.

PUBLISHER:

Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group

ISBN-10:

1400077958

ISBN-13:

9781400077953

BINDING:

Paperback

BOOK DIMENSIONS:

Dimensions: 5.2000(W) x Dimensions: 8.1600(H) x Dimensions: 0.5800(D)