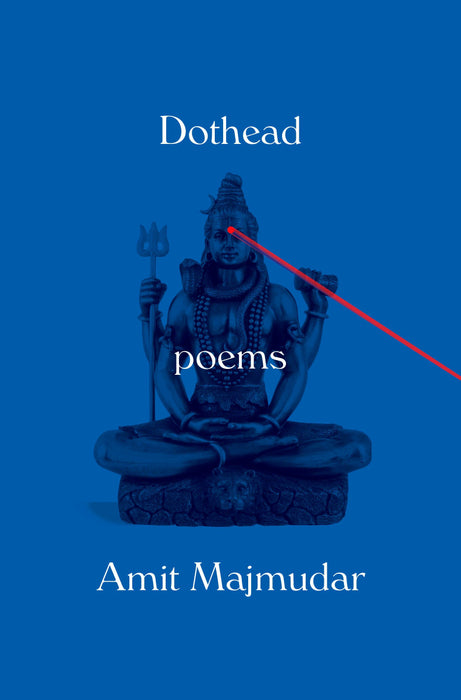

Dothead

Dothead is an exploration of selfhood both intense and exhilarating. Within the first pages, Amit Majmudar asserts the claims of both the self and the other: the title poem shows us the place of an Indian American teenager in the bland surround of a mostly white peer group, partaking of imagery from the poet’s Hindu tradition; the very next poem is a fanciful autobiography, relying for its imagery on the religious tradition of Islam. From poems about the treatment at the airport of people who look like Majmudar (“my dark unshaven brothers / whose names overlap with the crazies and God fiends”) to a long, freewheeling abecedarian poem about Adam and Eve and the discovery of oral sex, Dothead is a profoundly satisfying cultural critique and a thrilling experiment in language. United across a wide range of tones and forms, the poems inhabit and explode multiple perspectives, finding beauty in every one.

“Supurb….inventive, playful….Majmudar finds poetry in the modern world where we least expect it.”—Bookpage

“Especially perceptive about manhood and its meanings…Dothead is charming and urgent in equal measure.” —Dwight Garner, The New York Times

Library Journal listed DOTHEAD as one of their Spring poetry picks of 2016 for "pointedly offering commentary on those who aren't always at home in America."

"Dothead amounts to nothing less than a torrent of poetic inventiveness driven by the inexhaustible poetic energy of Amit Majmudar. His delight in deploying his formal skills combines remarkably with his wide range of interests to produce a collection of poetry both riveting and enviable. Drones, torture, immigration, weaponry, James Bond, King Lear, medical practice, Hinduism, and the sex life of Adam and Eve are but a few of the subjects treated here without any sacrifice of lyric texture or pulse. Majmudar stands out clearly and forcefully in the overpopulated tableau of contemporary American poetry.”—Billy Collins

“Readers new to Amit Majmudar’s work will rejoice to find themselves in the company of a writer who clearly believes no poem can enlighten unless it first entertains. We are invariably surprised—by Kafkaesque fable or Borgesian paradox, by fluently rhymed verse, a calligramme, or some outrageous form of his own invention. However Majmudar has Hardy’s knack of finding forms well suited to his subject, these wise, timely meditations on race, sex, language and identity leave us thinking about nothing more than the radical ideas they propose. All serve Majmudar’s larger project—to reflect the uncomfortable complexity of the human animal. He has no hesitation in juxtaposing the serious and the grave, the base and the transcendent, and those acts of gentleness and brutality which define us; but his ability to turn on a dime will often have the reader laughing or shivering before he has a chance to prepare his defences. Majmudar has allied an old-fashioned talent to a real experimental boldness, but perhaps the most startling aspect of his work is its unapologetic assumption of poetry’s intrinsic cultural value. One has the sense that every line simply believes in itself. The result is a various, wakeful, urgent poetry that asks to be read now.”—Don Paterson

www.amitmajmudar.comDothead

Well yes, I said, my mother wears a dot.

I know they said “third eye” in class, but it’s not

an eye eye, not like that. It’s not some freak

third eye that opens on your forehead like

on some Chernobyl baby. What it means

is, what it’s showing is, there’s this unseen

eye, on the inside. And she’s marking it.

It’s how the X that says where treasure’s at

is not the treasure, but as good as treasure.—

All right. What I said wasn’t half so measured.

In fact, I didn’t say a thing. Their laughter

had made my mouth go dry. Lunch was after

World History; that week was India—myths,

caste system, suttee, all the Greatest Hits.

The white kids I was sitting with were friends,

at least as I defined a friend back then.

So wait, said Nick, does your mom wear a dot?

I nodded, and I caught a smirk on Todd—

She wear it to the shower? And to bed?—

while Jesse sucked his chocolate milk and Brad

was getting ready for another stab.

I said, Hand me that ketchup packet there.

And Nick said, What? I snatched it, twitched the tear,

and squeezed a dollop on my thumb and worked

circles till the red planet entered the house of war

and on my forehead for the world to see

my third eye burned those schoolboys in their seats,

their flesh in little puddles underneath,

pale pools where Nataraja cooled his feet.

Ode to a Drone

Hell-raiser, razor-feathered

riser, windhover over

Peshawar,

power’s

joystick-blithe

thousand-mile scythe,

proxy executioner’s

proxy ax

pinged by a proxy server,

winged victory,

pilot cipher

unburdened by aught

but fuel and bombs,

fool of God, savage

idiot savant

sucking your benumbed

trigger-finger

gamer’s thumb

His Love of Semicolons

The comma is comely, the period, peerless,

but stack them one atop

the other, and I am in love; what I love

is the end that refuses to stop,

the promise that something will come in a moment

though the saying seem all said;

a grammatical afterlife, fullness that spills

past the full stop, not so much dead

as taking a breather, at worst, stunned;

the sentence regroups and restarts,

its notation bespeaking momentum, its silence

dividing the beats of a heart;

PUBLISHER:

Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group

ISBN-10:

1101947098

ISBN-13:

9781101947098

BINDING:

Paperback

BOOK DIMENSIONS:

Dimensions: 7.0000(W) x Dimensions: 9.1000(H) x Dimensions: 0.4000(D)