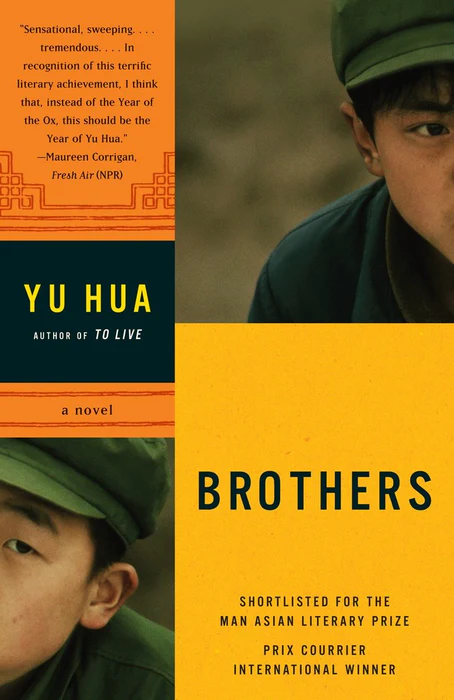

Brothers

by Anchor

Sold out

Original price

$22.00

-

Original price

$22.00

Original price

$22.00

$22.00

-

$22.00

Current price

$22.00

A bestseller in China, Brothers is an epic and wildly unhinged black comedy of modern Chinese society running amok.

Here is China as we've never seen it before, in a sweeping, Rabelaisian panorama of forty years of rough-and-rumble Chinese history, from the madness of the Cultural Revolution to the equally rabid madness of extreme materialism. Yu Hua, award-winning author of To Live, gives us a surreal tale of two comically mismatched stepbrothers, Baldy Li, a sex-obsessed ne'er-do-well, and the bookish, sensitive Song Gang, who vow that they will always be brothers—a bond they will struggle to maintain over the years as they weather the ups and downs of rivalry in love and making and losing millions in the new China.

Both tragic and absurd by turns, Brothers is a fascinating vision of an extraordinary place and time.“Sensational, sweeping. . . . tremendous. . . . In recognition of this terrific literary achievement, I think that, instead of the Year of the Ox, this should be the Year of Yu Hua.” —Maureen Corrigan, NPR’s Fresh Air

“Impressive . . . a family history documenting four decades of profound social and cultural transformation in China. . . . [and] an irreverent take on everything from the Cultural Revolution to the capitalist boom. . . . [A] relentlessly entertaining epic.” —The New Yorker

“Portraits of contemporary China are rarely sharper or more savage.” —Time

“[A] great literary achievement. . . . A sprawling, bawdy epic that crackles with life's joys, sorrows, and misadventures.” —The Boston Globe

“This new English translation of Brothers excellently captures its beauty and high farce.” —Time

“Waggish but merciless. . . . A consistently and terrifically funny read.” —Los Angeles Times

“A work of rare scope and grandeur. . . . [Yu Hua’s] sharply unadorned language is all his own, carrying a ripe and pungent tone. . . . This is the epic as plain-spoken brawl, one with blood on its face, a tear in the eye, and a grin on the lips. 10 out of 10 stars.” —Pop Matters

“For their translation Eileen Cheng-yin Chow and Carlos Rojas receive high marks, giving their narrator a consistent voice with palpable wit and visible verve, shortening Yu Hua’s sentences to fit English expectations but maintaining fidelity to the length and pace of his clauses, the real seat of an author’s prose style.” —Rain Taxi Review of Books

“Yu Hua’s epic novel—a bestseller in his native China—is a tale of ribaldry, farce and bloody revolution, a dramatic panorama of human vulgarity. . . . at once hyperrealist and phantasmagorical. . . . We can see a true picture of the country refracted in this funhouse mirror.” —The Washington Post

“Vigorous and racy. . . . This widely-ranging and ironic portrait of modern China evokes the very feel of the place, with its popular Korean TV soaps, Eternity bicycles, factory labor, Big White Rabbit candies, neon lights and raucous music. . . . A major achievement by any standard.” —Taipei Times

YU HUA is the author of five novels, six story collections, and four essay collections. He has also contributed op-ed pieces to The New York Times. His work has been translated into more than forty languages. He is the recipient of many awards, including the James Joyce Award, France's Prix Courrier International, and Italy's Premio Grinzane Cavour. He lives in Beijing.CHAPTER 1

Baldy li, our Liu Town’s premier tycoon, had a fantastic plan of spending twenty million U.S. dollars to purchase a ride on a Russian Federation space shuttle for a tour of outer space. Perched atop his famously gold-plated toilet seat, he would close his eyes and imagine himself already floating in orbit, surrounded by the unfathomably frigid depths of space. He would look down at the glorious planet stretched out beneath him, only to choke up on realizing that he had no family left down on Earth.

Baldy Li used to have a brother named Song Gang, who was a year older and a whole head taller and with whom he shared everything. Loyal, stubborn Song Gang had died three years earlier, reduced to a pile of ashes. When Baldy Li remembered the small wooden urn containing his brother’s remains, he had a million mixed emotions. The ashes from even a sapling, he thought, would outweigh those from Song Gang’s bones.

Back when Baldy Li’s mother was still alive, she always liked to speakto him about Song Gang as being a chip off the old block. She would emphasize how honest and kind he was, just like his father, and remark that father and son were like two melons from the same vine. When she talked about Baldy Li, she didn’t say this sort of thing but would emphatically shake her head. She said that Baldy Li and his father were completely different sorts of people, on completely different paths. It was not until Baldy Li’s fourteenth year, when he was nabbed for peeping at five women’s bottoms in a public pit toilet, that his mother drastically reversed her earlier opinion of her son. Only then did she finally understand that Baldy Li and his father were in fact two melons from the same vine after all. Baldy Li remembered clearly how his mother had averted her eyes and turned away from him, muttering bitterly as she wiped away her tears, “A chip off the old block.”

Baldy Li had never met his birth father, since on the day he was born his father left this earth in a fit of stink. His mother told him that his father had drowned, but Baldy Li asked, “How? Did he drown in the stream, in the pond, or in a well?” His mother didn’t respond. It was only later, after Baldy Li had been caught peeping and had become stinkingly notorious throughout Liu Town—only then did he learn that he really was another rotten melon off the same damn vine as his father. And it was only then that he learned that his father had also been peeping at women’s butts in a latrine when he accidentally fell into the cesspool and drowned. Everyone in Liu Town—men and women, young and old—laughed when they heard about Baldy Li and couldn’t stop repeating, “A chip off the old block.” As sure as a tree grows leaves, if you were from Liu Town, you would have the phrase on your lips; even toddlers who had just learned to speak were gurgling it. People pointed at Baldy Li, whispering to each other and covering their mouths and snickering, but Baldy Li would maintain an innocent expression as he continued on his way. Inside, however, he would be chuckling because now—at that time he was almost fifteen—he finally knew what it was to be a man.

Nowadays the world is filled with women’s bare butts shaking hither and thither, on television and in the movies, on VCRs and DVDs, i advertisements and magazines, on the sides of ballpoint pens and cigarette lighters. These include all sorts of butts: imported butts, domestic butts; white, yellow, black, and brown; big, small, fat, and thin; smooth and coarse, young and old, fake and real—every shape and size in a bedazzling variety. Nowadays women’s bare butts aren’t worth much, since they can be found virtually everywhere. But back then things were different. It used to be that women’s bottoms were considered a rare and precious commodity that you couldn’t trade for gold or silver or pearls. To see one, you had to go peeping in the public toilet—which is why you had a little hoodlum like Baldy Li being caught in the act, and a big hoodlum like his father losing his life for the sake of a glimpse.

Public toilets back then were different from today. Nowadays you wouldn’t be able to spy on a woman’s butt in a toilet even if you had a periscope, but back then there was only a flimsy partition between the men’s and women’s sections, below which there was a shared cesspool. On the other side of the partition the sounds of women peeing and shitting seemed disconcertingly close. So instead of squatting down where you should, you could poke your head under the partition, suspending yourself above the muck below by tightly gripping the boards with your hands and your legs. With the nauseating stench bringing tears to your eyes and maggots crawling all around, you could bend over like a competitive swimmer at the starting block about to dive into the pool, and the deeper you bent over, the more butt you would be able to see.

That time Baldy Li snared five butts with a single glance: a puny one, a fat one, two bony ones, and a just-right one, all lined up in a neat row, like slabs of meat in a butcher shop. The fat butt was like a fresh rump of pork, the two bony ones were like beef jerky, while the puny butt wasn’t even worth mentioning. The butt that Baldy Li fancied was the just-right one, which lay directly in his line of sight. It was the roundest of the five, so round it seemed to curl up, with taut skin revealing the faint outlines of a tailbone. His heart pounding, he wanted to glimpse the pubic area on the other side of the tailbone, so he continued to lean down, his head burrowing deeper under the partition. But just as he was about to catch a glimpse of her pubic region, he was suddenly nabbed.

A man named Victory Zhao, one of the two Men of Talent in Liu Town, happened to enter the latrine at that very moment. He spotted someone’s head and torso burrowing under the partition and immediately understood what was going on. He therefore grabbed Baldy Li by the scruff of his neck, plucking him up as one would a carrot. At that time Victory Zhao was in his twenties and had published a four-line poem in our provincial culture center’s mimeographed magazine, thereby earning himself the moniker Poet Zhao. After seizing Baldy Li, Zhao flushed bright red. He dragged the fourteen-year-old outside and started lecturing him nonstop, without, however, failing to be poetic: “So, rather than gazing at the glittering sea of sprouted greens in the fields or the fishes cavorting in the lake or the beautiful tufts of clouds in the blue sky, you choose instead to go snooping around in the toilet. . . .”

Poet Zhao went on in this vein for more than ten minutes, and yet there was still no movement from the women’s side of the latrine. Eventually Zhao became anxious, ran to the door, and yelled for the women to come out. Forgetting that he was an elegant man of letters, he shouted rather crudely, “Stop your pissing and shitting. You’ve been spied upon, and you don’t even realize it. Get your butts out here.”

The owners of the five butts finally dashed out, shrieking and weeping. The weeper was the puny butt not worth mentioning. A little girl eleven or twelve years old, she covered her face with her hands and was crying so hard she trembled, as if Baldy Li hadn’t peeped at her but, rather, had raped her. Baldy Li, still standing there in Poet Zhao’s grip, watched the weeping little butt and thought, What’s all this crying over your underdeveloped little butt? I only took a look because there wasn’t much else I could do.

A pretty seventeen-year-old was the last to emerge. Blushing furiously, she took a quick look at Baldy Li and hurried away. Poet Zhao cried out for her not to leave, to come back and demand justice. Instead, she simply hurried away even faster. Baldy Li watched the swaying of her rear end as she walked, and knew that the butt so round it curled up had to be hers.

Once the round butt disappeared into the distance and the weeping little butt also left, one of the bony butts started screeching at Baldy Li,

spraying his face with spittle. Then she wiped her mouth and walked off as well. Baldy Li watched her walk away and noticed that her butt

was so flat that, now that she had her pants on, you couldn’t even make it out.

The remaining three—an animated Poet Zhao, a pork-rump butt, and the other jerky-flat butt—then grabbed Baldy Li and hauled him to the police station. They marched him through the little town of less than fifty thousand, and along the way the town’s other Man of Talent, Success Liu, joined their ranks. Like Poet Zhao, Success Liu was in his twenties and had had something published in the culture center’s magazine. His publication was a story, its words crammed onto two pages. Compared with Zhao’s four lines of verse, Success Liu’s two pages were far more impressive, thereby earning him the nickname Writer Liu. Liu didn’t lose out to Poet Zhao in terms of monikers, and he certainly couldn’t lose out to him in other areas either. Writer Liu was on his way to buy rice when he saw Poet Zhao strutting toward him with a captive Baldy Li, and Liu immediately decided that he couldn’t let Poet Zhao have all the glory to himself. Writer Liu hollered to Poet Zhao as he approached, “I’m here to help you!”

Poet Zhao and Writer Liu were close writing comrades, and Writer Liu had once searched high and low for the perfect encomia for Poet

Zhao’s four lines of poetry. Poet Zhao of course had responded in kind and found even more flowery praise for Writer Liu’s two pages of text. Poet Zhao was originally walking behind Baldy Li, with the miscreant in his grip, but now that Writer Liu hustled up to them, Poet Zhao shifted to the left and offered Writer Liu the position to the right. Liu Town’s two Men of Talent flanked Baldy Li, proclaiming that they were

taking him to the police station. There was actually a station just around the corner, but they didn’t want to take him there; instead, they

marched him to one much farther away. On their way, they paraded down the main streets, trying to maximize their moment of glory. As

they escorted Baldy Li through the streets they remarked enviously, “Just look at you, with two important men like us escorting you. You

really are a lucky guy.” Poet Zhao added, “It’s as if you were being escorted by Li Bai and Du Fu. . . .”

It seemed to Writer Liu that Poet Zhao’s analogy was not quite apt, since Li Bai and Du Fu were, of course, both poets, while Liu himself wrote fiction. So he corrected Zhao, saying, “It’s as if Li Bai and Cao Xueqin were escorting you. . . .”

Baldy Li had initially ignored their banter, but when he heard Liu Town’s two Men of Talent compare themselves to Li Bai and Cao Xueqin, he couldn’t help but laugh. “Hey, even I know that Li Bai was from the Tang dynasty while Cao was from the Qing dynasty,” he said. “So how can a Tang guy be hanging out with a Qing guy?” The crowds that had gathered alongside the street burst into loud guffaws. They said that Baldy Li was absolutely correct, that Liu Town’s two Men of Talent might indeed be full of talent, but their knowledge of history wasn’t a match even for this little Peeping Tom. The two Men of Talent blushed furiously, and Poet Zhao, straightening his neck, added, “It’s just an analogy.”

“Or we could use another analogy,” offered Writer Liu. “Given that it’s a poet and a novelist escorting you, we should say we are Guo

Moruo and Lu Xun.” The crowd expressed their approval. Even Baldy Li nodded and said, “That’s more like it.”

Poet Zhao and Writer Liu didn’t dare say any more on the subject of literature. Instead, they grabbed Baldy Li’s collar and denounced his

hooligan behavior to one and all while continuing to march sternly ahead. Along the way, Baldy Li saw a great many people tittering at him, including some he knew and others he didn’t. Poet Zhao and Writer Liu took time to explain to everyone they met what had happened, appearing even more polished than talk-show hosts. And those two women who had had their butts peeped at by Baldy Li were like the special guests on their talk shows, looking alternately furious and aggrieved as they responded to Poet Zhao and Writer Liu’s recounting of events. As the women walked along, the one with a fat butt suddenly screeched, having noticed her own husband among the spectators, and started sobbing as she complained loudly, “He saw my bottom and god knows what else! Whip him!”

Here is China as we've never seen it before, in a sweeping, Rabelaisian panorama of forty years of rough-and-rumble Chinese history, from the madness of the Cultural Revolution to the equally rabid madness of extreme materialism. Yu Hua, award-winning author of To Live, gives us a surreal tale of two comically mismatched stepbrothers, Baldy Li, a sex-obsessed ne'er-do-well, and the bookish, sensitive Song Gang, who vow that they will always be brothers—a bond they will struggle to maintain over the years as they weather the ups and downs of rivalry in love and making and losing millions in the new China.

Both tragic and absurd by turns, Brothers is a fascinating vision of an extraordinary place and time.“Sensational, sweeping. . . . tremendous. . . . In recognition of this terrific literary achievement, I think that, instead of the Year of the Ox, this should be the Year of Yu Hua.” —Maureen Corrigan, NPR’s Fresh Air

“Impressive . . . a family history documenting four decades of profound social and cultural transformation in China. . . . [and] an irreverent take on everything from the Cultural Revolution to the capitalist boom. . . . [A] relentlessly entertaining epic.” —The New Yorker

“Portraits of contemporary China are rarely sharper or more savage.” —Time

“[A] great literary achievement. . . . A sprawling, bawdy epic that crackles with life's joys, sorrows, and misadventures.” —The Boston Globe

“This new English translation of Brothers excellently captures its beauty and high farce.” —Time

“Waggish but merciless. . . . A consistently and terrifically funny read.” —Los Angeles Times

“A work of rare scope and grandeur. . . . [Yu Hua’s] sharply unadorned language is all his own, carrying a ripe and pungent tone. . . . This is the epic as plain-spoken brawl, one with blood on its face, a tear in the eye, and a grin on the lips. 10 out of 10 stars.” —Pop Matters

“For their translation Eileen Cheng-yin Chow and Carlos Rojas receive high marks, giving their narrator a consistent voice with palpable wit and visible verve, shortening Yu Hua’s sentences to fit English expectations but maintaining fidelity to the length and pace of his clauses, the real seat of an author’s prose style.” —Rain Taxi Review of Books

“Yu Hua’s epic novel—a bestseller in his native China—is a tale of ribaldry, farce and bloody revolution, a dramatic panorama of human vulgarity. . . . at once hyperrealist and phantasmagorical. . . . We can see a true picture of the country refracted in this funhouse mirror.” —The Washington Post

“Vigorous and racy. . . . This widely-ranging and ironic portrait of modern China evokes the very feel of the place, with its popular Korean TV soaps, Eternity bicycles, factory labor, Big White Rabbit candies, neon lights and raucous music. . . . A major achievement by any standard.” —Taipei Times

YU HUA is the author of five novels, six story collections, and four essay collections. He has also contributed op-ed pieces to The New York Times. His work has been translated into more than forty languages. He is the recipient of many awards, including the James Joyce Award, France's Prix Courrier International, and Italy's Premio Grinzane Cavour. He lives in Beijing.CHAPTER 1

Baldy li, our Liu Town’s premier tycoon, had a fantastic plan of spending twenty million U.S. dollars to purchase a ride on a Russian Federation space shuttle for a tour of outer space. Perched atop his famously gold-plated toilet seat, he would close his eyes and imagine himself already floating in orbit, surrounded by the unfathomably frigid depths of space. He would look down at the glorious planet stretched out beneath him, only to choke up on realizing that he had no family left down on Earth.

Baldy Li used to have a brother named Song Gang, who was a year older and a whole head taller and with whom he shared everything. Loyal, stubborn Song Gang had died three years earlier, reduced to a pile of ashes. When Baldy Li remembered the small wooden urn containing his brother’s remains, he had a million mixed emotions. The ashes from even a sapling, he thought, would outweigh those from Song Gang’s bones.

Back when Baldy Li’s mother was still alive, she always liked to speakto him about Song Gang as being a chip off the old block. She would emphasize how honest and kind he was, just like his father, and remark that father and son were like two melons from the same vine. When she talked about Baldy Li, she didn’t say this sort of thing but would emphatically shake her head. She said that Baldy Li and his father were completely different sorts of people, on completely different paths. It was not until Baldy Li’s fourteenth year, when he was nabbed for peeping at five women’s bottoms in a public pit toilet, that his mother drastically reversed her earlier opinion of her son. Only then did she finally understand that Baldy Li and his father were in fact two melons from the same vine after all. Baldy Li remembered clearly how his mother had averted her eyes and turned away from him, muttering bitterly as she wiped away her tears, “A chip off the old block.”

Baldy Li had never met his birth father, since on the day he was born his father left this earth in a fit of stink. His mother told him that his father had drowned, but Baldy Li asked, “How? Did he drown in the stream, in the pond, or in a well?” His mother didn’t respond. It was only later, after Baldy Li had been caught peeping and had become stinkingly notorious throughout Liu Town—only then did he learn that he really was another rotten melon off the same damn vine as his father. And it was only then that he learned that his father had also been peeping at women’s butts in a latrine when he accidentally fell into the cesspool and drowned. Everyone in Liu Town—men and women, young and old—laughed when they heard about Baldy Li and couldn’t stop repeating, “A chip off the old block.” As sure as a tree grows leaves, if you were from Liu Town, you would have the phrase on your lips; even toddlers who had just learned to speak were gurgling it. People pointed at Baldy Li, whispering to each other and covering their mouths and snickering, but Baldy Li would maintain an innocent expression as he continued on his way. Inside, however, he would be chuckling because now—at that time he was almost fifteen—he finally knew what it was to be a man.

Nowadays the world is filled with women’s bare butts shaking hither and thither, on television and in the movies, on VCRs and DVDs, i advertisements and magazines, on the sides of ballpoint pens and cigarette lighters. These include all sorts of butts: imported butts, domestic butts; white, yellow, black, and brown; big, small, fat, and thin; smooth and coarse, young and old, fake and real—every shape and size in a bedazzling variety. Nowadays women’s bare butts aren’t worth much, since they can be found virtually everywhere. But back then things were different. It used to be that women’s bottoms were considered a rare and precious commodity that you couldn’t trade for gold or silver or pearls. To see one, you had to go peeping in the public toilet—which is why you had a little hoodlum like Baldy Li being caught in the act, and a big hoodlum like his father losing his life for the sake of a glimpse.

Public toilets back then were different from today. Nowadays you wouldn’t be able to spy on a woman’s butt in a toilet even if you had a periscope, but back then there was only a flimsy partition between the men’s and women’s sections, below which there was a shared cesspool. On the other side of the partition the sounds of women peeing and shitting seemed disconcertingly close. So instead of squatting down where you should, you could poke your head under the partition, suspending yourself above the muck below by tightly gripping the boards with your hands and your legs. With the nauseating stench bringing tears to your eyes and maggots crawling all around, you could bend over like a competitive swimmer at the starting block about to dive into the pool, and the deeper you bent over, the more butt you would be able to see.

That time Baldy Li snared five butts with a single glance: a puny one, a fat one, two bony ones, and a just-right one, all lined up in a neat row, like slabs of meat in a butcher shop. The fat butt was like a fresh rump of pork, the two bony ones were like beef jerky, while the puny butt wasn’t even worth mentioning. The butt that Baldy Li fancied was the just-right one, which lay directly in his line of sight. It was the roundest of the five, so round it seemed to curl up, with taut skin revealing the faint outlines of a tailbone. His heart pounding, he wanted to glimpse the pubic area on the other side of the tailbone, so he continued to lean down, his head burrowing deeper under the partition. But just as he was about to catch a glimpse of her pubic region, he was suddenly nabbed.

A man named Victory Zhao, one of the two Men of Talent in Liu Town, happened to enter the latrine at that very moment. He spotted someone’s head and torso burrowing under the partition and immediately understood what was going on. He therefore grabbed Baldy Li by the scruff of his neck, plucking him up as one would a carrot. At that time Victory Zhao was in his twenties and had published a four-line poem in our provincial culture center’s mimeographed magazine, thereby earning himself the moniker Poet Zhao. After seizing Baldy Li, Zhao flushed bright red. He dragged the fourteen-year-old outside and started lecturing him nonstop, without, however, failing to be poetic: “So, rather than gazing at the glittering sea of sprouted greens in the fields or the fishes cavorting in the lake or the beautiful tufts of clouds in the blue sky, you choose instead to go snooping around in the toilet. . . .”

Poet Zhao went on in this vein for more than ten minutes, and yet there was still no movement from the women’s side of the latrine. Eventually Zhao became anxious, ran to the door, and yelled for the women to come out. Forgetting that he was an elegant man of letters, he shouted rather crudely, “Stop your pissing and shitting. You’ve been spied upon, and you don’t even realize it. Get your butts out here.”

The owners of the five butts finally dashed out, shrieking and weeping. The weeper was the puny butt not worth mentioning. A little girl eleven or twelve years old, she covered her face with her hands and was crying so hard she trembled, as if Baldy Li hadn’t peeped at her but, rather, had raped her. Baldy Li, still standing there in Poet Zhao’s grip, watched the weeping little butt and thought, What’s all this crying over your underdeveloped little butt? I only took a look because there wasn’t much else I could do.

A pretty seventeen-year-old was the last to emerge. Blushing furiously, she took a quick look at Baldy Li and hurried away. Poet Zhao cried out for her not to leave, to come back and demand justice. Instead, she simply hurried away even faster. Baldy Li watched the swaying of her rear end as she walked, and knew that the butt so round it curled up had to be hers.

Once the round butt disappeared into the distance and the weeping little butt also left, one of the bony butts started screeching at Baldy Li,

spraying his face with spittle. Then she wiped her mouth and walked off as well. Baldy Li watched her walk away and noticed that her butt

was so flat that, now that she had her pants on, you couldn’t even make it out.

The remaining three—an animated Poet Zhao, a pork-rump butt, and the other jerky-flat butt—then grabbed Baldy Li and hauled him to the police station. They marched him through the little town of less than fifty thousand, and along the way the town’s other Man of Talent, Success Liu, joined their ranks. Like Poet Zhao, Success Liu was in his twenties and had had something published in the culture center’s magazine. His publication was a story, its words crammed onto two pages. Compared with Zhao’s four lines of verse, Success Liu’s two pages were far more impressive, thereby earning him the nickname Writer Liu. Liu didn’t lose out to Poet Zhao in terms of monikers, and he certainly couldn’t lose out to him in other areas either. Writer Liu was on his way to buy rice when he saw Poet Zhao strutting toward him with a captive Baldy Li, and Liu immediately decided that he couldn’t let Poet Zhao have all the glory to himself. Writer Liu hollered to Poet Zhao as he approached, “I’m here to help you!”

Poet Zhao and Writer Liu were close writing comrades, and Writer Liu had once searched high and low for the perfect encomia for Poet

Zhao’s four lines of poetry. Poet Zhao of course had responded in kind and found even more flowery praise for Writer Liu’s two pages of text. Poet Zhao was originally walking behind Baldy Li, with the miscreant in his grip, but now that Writer Liu hustled up to them, Poet Zhao shifted to the left and offered Writer Liu the position to the right. Liu Town’s two Men of Talent flanked Baldy Li, proclaiming that they were

taking him to the police station. There was actually a station just around the corner, but they didn’t want to take him there; instead, they

marched him to one much farther away. On their way, they paraded down the main streets, trying to maximize their moment of glory. As

they escorted Baldy Li through the streets they remarked enviously, “Just look at you, with two important men like us escorting you. You

really are a lucky guy.” Poet Zhao added, “It’s as if you were being escorted by Li Bai and Du Fu. . . .”

It seemed to Writer Liu that Poet Zhao’s analogy was not quite apt, since Li Bai and Du Fu were, of course, both poets, while Liu himself wrote fiction. So he corrected Zhao, saying, “It’s as if Li Bai and Cao Xueqin were escorting you. . . .”

Baldy Li had initially ignored their banter, but when he heard Liu Town’s two Men of Talent compare themselves to Li Bai and Cao Xueqin, he couldn’t help but laugh. “Hey, even I know that Li Bai was from the Tang dynasty while Cao was from the Qing dynasty,” he said. “So how can a Tang guy be hanging out with a Qing guy?” The crowds that had gathered alongside the street burst into loud guffaws. They said that Baldy Li was absolutely correct, that Liu Town’s two Men of Talent might indeed be full of talent, but their knowledge of history wasn’t a match even for this little Peeping Tom. The two Men of Talent blushed furiously, and Poet Zhao, straightening his neck, added, “It’s just an analogy.”

“Or we could use another analogy,” offered Writer Liu. “Given that it’s a poet and a novelist escorting you, we should say we are Guo

Moruo and Lu Xun.” The crowd expressed their approval. Even Baldy Li nodded and said, “That’s more like it.”

Poet Zhao and Writer Liu didn’t dare say any more on the subject of literature. Instead, they grabbed Baldy Li’s collar and denounced his

hooligan behavior to one and all while continuing to march sternly ahead. Along the way, Baldy Li saw a great many people tittering at him, including some he knew and others he didn’t. Poet Zhao and Writer Liu took time to explain to everyone they met what had happened, appearing even more polished than talk-show hosts. And those two women who had had their butts peeped at by Baldy Li were like the special guests on their talk shows, looking alternately furious and aggrieved as they responded to Poet Zhao and Writer Liu’s recounting of events. As the women walked along, the one with a fat butt suddenly screeched, having noticed her own husband among the spectators, and started sobbing as she complained loudly, “He saw my bottom and god knows what else! Whip him!”

PUBLISHER:

Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group

ISBN-10:

0307386066

ISBN-13:

9780307386069

BINDING:

Paperback

BOOK DIMENSIONS:

Dimensions: 5.1600(W) x Dimensions: 7.9600(H) x Dimensions: 1.1100(D)