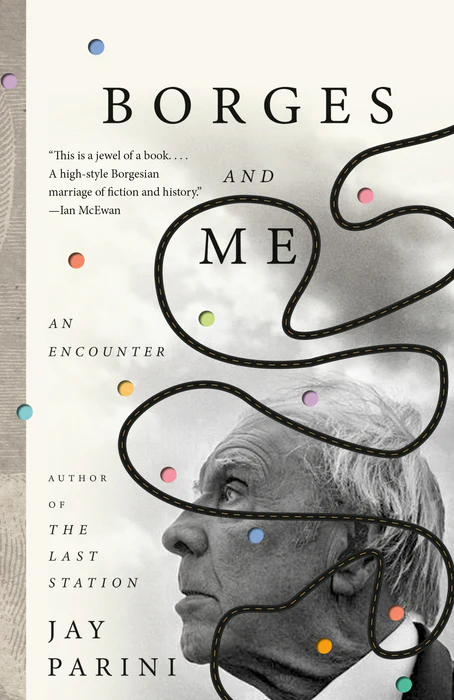

Borges and Me

by Anchor

In this evocative work of what the author in his afterword calls “a kindof novelistic memoir,” Jay Parini takes us back fifty years, when he fled the United States for Scotland—in flight from the Vietnam War and desperately in search of his adult life. There, through unlikely circumstances, he meets the famed Argentinian author Jorge Luis Borges.

Borges—visiting his translator in Scotland—is in his seventies, blind and frail. When Borges hears that Parini owns a 1957 Morris Minor, he declares a long-held wish to visit the Highlands, where he hopes to meet a man in Inverness who is interested in Anglo-Saxon riddles. As they travel, stopping at various sites of historical interest, the charmingly garrulous Borges takes Parini on a grand tour of Western literature and ideas, while promising to teach him about love and poetry. As Borges’s idiosyncratic world of labyrinths, mirrors, and doubles shimmers into being, their escapades take a surreal turn.

Borges and Me is a classic road novel, based on true events. It’s also a magical mystery tour of an era, like our own, in which uncertainties abound, and when—as ever—it’s the young and the old who hear voices and dream dreams.“This is a jewel of a book. . . . A high-style Borgesianmarriage of fiction and history.” —Ian McEwan

“A classic comic-philosophical road story, playfully conscious of its own traditions.” —The Wall Street Journal

“A delicious treat. . . . This reminiscence by Parini, who is now a prolific novelist, biographer and poet, brings Borges more sharply to life than any account I’ve read or heard.” —Michael Greenberg, The New York Times Book Review

“One of the great books of our time.” —Michael Silverblatt, Bookworm, KCRW

“A tender bond forms between the eccentric sage and his caretaker. . . . Fans of both Borges and Parini will delight in this touching coming-of-age memoir.” —Publishers Weekly (starred review)

“A captivating chronicle and homage.” —Kirkus Reviews

“Borges and Me is a road-trip book like no other, written by someone who certainly didn’t spend his youth the way I did. I loved every minute of reading it. It’s full of wonderful energy and humor, with underpinnings of sadness and seriousness I can’t shake.” —Ann Beattie

“A loving portrait of [a] singular writer. . . . As Parini chronicles their misadventures with the hilarity of hindsight, he palpably re-creates his youthful anxiety and Borges’ own sometimes infuriating sanguinity.” —BookPageJay Parini is a poet, novelist, and biographer who teaches at Middlebury College. He has written eight novels, including The Damascus Road, Benjamin’s Crossing, The Apprentice Lover, The Passages of H.M., and The Last Station, the last made into an Academy Award–nominated film. His biographical subjects include John Steinbeck, Robert Frost, William Faulkner, and, most recently, Gore Vidal. His nonfiction works include Jesus: The Human Face of God, Why Poetry Matters, and Promised Land: Thirteen Books That Changed America.Chapter 1

One June morning in 1986, at my farmhouse in Vermont, I stepped from bed as the sun had only just lifted an eyebrow over the Green Mountains: always a coveted moment in my day, when I lean into beginnings, thinking about the work ahead of me—in this case, a novel about the last days of Tolstoy that had begun to glimmer at the edges of my conscious mind. My wife and children were still asleep, and I couldn’t help but look at them fondly. How could I resist these sweet little boys who drove me nuts at times, as children must do, as it’s their job? Or a bright, affectionate wife who didn’t seem to mind my occasional flights of idiocy, offering a rueful smile at times, sometimes a deep laugh? This bounty felt undeserved and probably was. With a sense of gratitude, even amazement, I made my way downstairs into the country kitchen, where I brewed a strong cup of Irish Breakfast tea for myself before going into my study at the other end of the house.

As I often did before settling at the stained trestle table that still anchors my study, I turned on the radio to catch the headlines, tuning into the BBC on a shortwave radio that my old friend and mentor, Alastair Reid, had recently given to me as a gift for my thirty-eighth birthday. When the newscaster read the day’s top stories, I was stunned to hear that Jorge Luis Borges, the great Argentine writer “who blended fact and fiction in a peerless sequence of narratives that defied all boundaries and set off the Boom in Latin American literature,” had died in Geneva at the age of eighty-six. “He was a man of many stories,” the announcer said. “As a writer, he explored the most idiosyncratic spaces in the human experience, a lover of labyrinths and mirrors, a shapeshifting writer who could never be defined.”

Memories surfaced now. I had met Borges when I was a graduate student many years before, in Scotland, and traveled with him from St. Andrews to the Highlands and back. Our encounter lasted only a week or so, but it forced a shift in me, a change of perspective, hitting me at just the right time. And all I knew for sure was that my way of being in the world was never quite the same after Borges.

Standing at the window, I looked into the garden below at a bed of Oriental poppies, the blood-bright cheeks of the flowers turning toward me. Did they notice my stinging eyes? I thought so, and stepped away from the window. I’m not someone who cries easily, but I wept that day. Weeping as much for myself as for Borges, remembering the callow, overly serious, shy, and often terrified fellow I was when we met, trying to weigh this against the man I’d become, still wondering what on earth had happened to me in Scotland some fifteen years before.

—

In 1970, having just graduated from Lafayette College and moved (briefly, I hoped) back in with my parents in Scranton, Pennsylvania, I saw two choices: stay at home, where my mother would chop off my balls, or go to Vietnam, where they’d be blown off by a landmine. A third choice, less apparent at first but finally obvious, was to leave the United States altogether, getting as far away as possible. The place that called to me was a small town on the East Neuk of Fife, in Scotland.

St. Andrews had already provided me with a much-needed escape and given me a feeling of vocation, as I’d studied there for my junior year abroad. During a memorable year, I’d made friends easily, much to my surprise, mixing with Scottish and English students, befriending a handful of Continental students, too. The lectures I attended were often appealing—florid rhetorical performances of a kind unfamiliar to me—and I’d learned a good deal, especially from intense one-on-one tutorials with a range of eccentric but erudite teachers. (One of them held tutorials at his ramshackle flat, where his wife served us tea wearing a face mask as she was “sensitive to germs.”)

Most important, in Scotland I’d begun to write, recording my daily life in a journal, which I hoped (mentally cribbing a phrase from Robert Lowell) would shimmer with “the grace of accuracy.” No detail seemed too inconsequential to record, and I often filled pages with quotations from things I’d read or recorded snippets of conversation I’d overheard in tea shops or pubs. I also began to write my own poems. They were imitative and unmemorable, as one might expect, but this was a thrilling turn. I’d decided—for reasons based on no demonstrable talent or experience—to make a profession of writing.

I thought I knew quite a bit about literature, though I had a skim of learning, the lightest froth on a cup which was not even an especially big cup. Nonetheless, I’d begun to read with a sense of urgency. I gulped more than read books like Walden and Leaves of Grass, The Great Gatsby and Look Homeward, Angel. I scooped up Hesse, Woolf, Kerouac, Lawrence, McCullers, Nabokov, Beckett, and others. In libraries I leafed eagerly through the large, crisp pages of The New York Review of Books, drawn to provocative pieces by the likes of Gore Vidal, Joan Didion, Norman Mailer, and Susan Sontag. I attended readings by writers, some of them famous (Allen Ginsberg, James Dickey, Paul Goodman), and felt quite sure that literature would provide access to worlds far beyond Scranton.

I set my sights on graduate study in St. Andrews, though I knew it would be a battle to persuade my parents that this sort of move made sense. I was my mother’s first child, and she had been possessive from the first breath I drew. (My sister, Dorrie, was two years behind me, and her being a girl did not make it any easier with my mother, to put it mildly.) I was “backward,” my mother frequently said, which meant I was frightened by strangers, put off by everyone and everything. As a baby, I screamed whenever somebody unfamiliar stepped into the room. Only my mother could comfort me, and she encouraged this dependence. It wasn’t intentionally smothering, I suspect, but the results were the same. Needless to say, I would have great difficulty separating from her. Adulthood seemed a far, impossible kingdom.

My mother all but had a nervous breakdown when I left for Scotland the first time. “You’re going where?” she asked. “Scotland? Are you crazy? Nobody goes to Scotland!” The night before my first departure, in 1968, she hurled herself onto the bed in the hotel in New York in a state of emotional disarray. Her bitter wailing kept me awake in the adjacent room throughout the night, and she looked exhausted when she said goodbye to me at the docks the next morning, hardly uttering a word. I sailed away to Britain on a rickety Italian liner that she told me “was unstable and would probably sink.” It’s no wonder I wept quietly in my bunk on that low-rent ship on the eight-day journey from New York to Southampton. This was a kind of weaning for me, as I now see. I was shedding my old life as best I could. I could easily imagine my mother crying herself to sleep in Scranton, night after night, but I steeled myself, knowing that I had to go through whatever lay before me, no matter how painful.

My father was a genial worrywart, the son of Italian immigrants who spoke very little English and could offer their five sons few advantages beyond bowls of handmade linguini and homegrown vegetables. (My grandmother shot rabbits from her back porch and turned them into ragu.) Like many of his generation, children of the Great Depression, my father suffered from a pervasive cautiousness. The sidewalks of his mind were strewn with banana peels. He had been forced to leave high school well before graduating, but with a bit of luck and grit he made his way in the insurance business, selling local families policies that (I fear) he never quite understood himself. Every day he wore a suit with a starched white shirt and a colorful silk tie, holding his head high in Scranton. He polished his shoes before leaving the house with an exaggerated fervor. He had “made it.” And yet he continued to worry intensely about the future, especially my future.

So did I, and I was given a bottle of tranquilizers (old-fashioned barbiturates that would have stunned a horse) by our family doctor “to steady my nerves” before I set off to graduate school. “Don’t be so anxious,” Dr. Evans said to me. “All this nervousness isn’t good for you. If you stay up all night, you won’t get enough sleep. Just take the pills and stop worrying.”

So what exactly was I worried about? Pretty much everything, I think. The tidal wave of sex, drugs, and rock and roll on which my peers gleefully surfed felt to me more like a sea I might drown in. I was a virgin and afraid I might stay one forever. And more than anything, I was terrified of Vietnam, furious about a war fought over an illusion of freedom or world dominance or—more probably—something I couldn’t even imagine.

I had turned against the war during my freshman year in college, marching on Washington in 1967 and again in the spring of 1970. Like most college kids, I knew what I thought I knew: the war in Southeast Asia was immoral, stupid, and cruel. The antiwar writings of Howard Zinn, Noam Chomsky, and others became part of my permanent mental library. Making matters worse, my draft board had recently taken an interest in me, shifting my status after graduation from 2-S (student deferment) to 1-A (fit for active duty), even though I had drawn a reasonably high number in the lottery. I never quite metabolized this lucky draw and feared the worst, as my draft board in Lackawanna County was notorious, a prolific maw that gobbled up young men. Several of my friends from high school had been swept into the army, and one of them would soon end up in some godforsaken camp near the DMZ.

I still have nightmares about that morning at the armory in Scranton when, standing naked in line with dozens of others, I was prodded and poked by army doctors. “You call that a prick?” one sergeant yelled as I tried to hide my shriveled penis, which prompted barking laughter at my expense. One skinny guy I’d known from a tenth-grade physics class was there, and he passed out cold on the floor, foaming at the mouth, drawing his knees into a fetal position. “Send him first,” one of the recruiters said. “He’ll scare the shit out of them gooks.”

My mother was as determined as I was to keep me out of the action. Though I passed the army physical with flying colors, she was convinced I was unfit for service. “Think about your allergies. All night as a young boy you were coughing. That wheeze! You kept your poor sister awake all night. You still cough too much, especially in the spring, with the flowers, and it would keep the other soldiers awake in the barracks. They have enough to deal with in Vietnam without your health problems.” She had no end of schemes to keep me out of the military. As she wrote in one letter during my senior year in college, “Your Uncle Julie is well connected, and he knows a doctor who will certify that you can hardly breathe. Think how your chest feels when you exert yourself! And those feet of yours, without the arches. You couldn’t walk more than a few miles without sitting. What kind of army wants that? And by the way: Stop being so political. Why did you have to march on Washington, not once but twice? You’re not one of those hippies. You don’t understand as much about these things as you think you do.”

I spent many nights in the summer of 1970 arguing about the war with family and friends, especially Billy Giordano (as I will call him here), who had been a companion for some years, playing on my baseball team in junior high, joining me in pickup football after school in the fall, sometimes camping with me in the Poconos. He wasn’t a “smart kid,” as they say: not in any academic way. But I liked his freshness, his energy, and the kind of wild, subversive intelligence that doesn’t show up on exams. I made a point of seeking him out in the cafeteria at West Scranton High and finding ways to hang around him.

“This is our time,” he said only a day or so before he enlisted in the infantry that July, doing this “to avoid the draft”—a move that was perversely illogical and self-defeating. Unless, of course, what you really wanted was to go to Vietnam. “My dad was in the war against Hitler and Tojo,” he told me, “and he never regretted it. He thinks I should go.”

“Does he think I should go?”

“You should do whatever the fuck you want.”

When Billy came over to my house for a final visit before his induction, it was hard to look at him closely: the once innocently smooth face had become craggy, full of worry lines that summer. He had somehow broken a front tooth, which gave his smile a threatening appearance. He’d let his beard grow, unevenly; it showed itself in clumps of bristle on his cheeks and chin. His long and greasy hair brushed against his shoulders, and his neck needed shaving. He smelled of beer and cigarettes, had grown a little heavy, and spoke with a kind of pressured speech, as if History itself leaned over his shoulder and listened. Images of him at various stages in his adolescence floated in my head as I watched him talking. I saw him beside me in a canoe, fishing on some remote pond. Or dancing in the high school gym, making a fool of himself by leaping onto a table and bobbing his head obscenely to the lyrics of “Barbara Ann.” I always hoped to pitch on the baseball team in high school, and Billy was a gifted catcher who would let me throw lousy pitch after pitch into the dwindling pink-orange dusk at the sandlot field in Keyser Valley. When dark fell, we would sit together under a canopy of stars on the railroad tracks, talking about the nature and strangeness of life.

“I don’t know if there’s a God,” Billy had said to me once, “but there is pussy in the world. And I want to get as much of it as I can before I die. I do, yes, dear God.” I didn’t know whether or not to believe him, but I found his stories irresistible. And I loved Billy in part for the fearless way he lived his life. He took risks, and he encouraged me—without much success—to take risks. “If you don’t lay it on the line, Jay,” he would say, “what is the fucking point? Is there a fucking point?”

Borges—visiting his translator in Scotland—is in his seventies, blind and frail. When Borges hears that Parini owns a 1957 Morris Minor, he declares a long-held wish to visit the Highlands, where he hopes to meet a man in Inverness who is interested in Anglo-Saxon riddles. As they travel, stopping at various sites of historical interest, the charmingly garrulous Borges takes Parini on a grand tour of Western literature and ideas, while promising to teach him about love and poetry. As Borges’s idiosyncratic world of labyrinths, mirrors, and doubles shimmers into being, their escapades take a surreal turn.

Borges and Me is a classic road novel, based on true events. It’s also a magical mystery tour of an era, like our own, in which uncertainties abound, and when—as ever—it’s the young and the old who hear voices and dream dreams.“This is a jewel of a book. . . . A high-style Borgesianmarriage of fiction and history.” —Ian McEwan

“A classic comic-philosophical road story, playfully conscious of its own traditions.” —The Wall Street Journal

“A delicious treat. . . . This reminiscence by Parini, who is now a prolific novelist, biographer and poet, brings Borges more sharply to life than any account I’ve read or heard.” —Michael Greenberg, The New York Times Book Review

“One of the great books of our time.” —Michael Silverblatt, Bookworm, KCRW

“A tender bond forms between the eccentric sage and his caretaker. . . . Fans of both Borges and Parini will delight in this touching coming-of-age memoir.” —Publishers Weekly (starred review)

“A captivating chronicle and homage.” —Kirkus Reviews

“Borges and Me is a road-trip book like no other, written by someone who certainly didn’t spend his youth the way I did. I loved every minute of reading it. It’s full of wonderful energy and humor, with underpinnings of sadness and seriousness I can’t shake.” —Ann Beattie

“A loving portrait of [a] singular writer. . . . As Parini chronicles their misadventures with the hilarity of hindsight, he palpably re-creates his youthful anxiety and Borges’ own sometimes infuriating sanguinity.” —BookPageJay Parini is a poet, novelist, and biographer who teaches at Middlebury College. He has written eight novels, including The Damascus Road, Benjamin’s Crossing, The Apprentice Lover, The Passages of H.M., and The Last Station, the last made into an Academy Award–nominated film. His biographical subjects include John Steinbeck, Robert Frost, William Faulkner, and, most recently, Gore Vidal. His nonfiction works include Jesus: The Human Face of God, Why Poetry Matters, and Promised Land: Thirteen Books That Changed America.Chapter 1

One June morning in 1986, at my farmhouse in Vermont, I stepped from bed as the sun had only just lifted an eyebrow over the Green Mountains: always a coveted moment in my day, when I lean into beginnings, thinking about the work ahead of me—in this case, a novel about the last days of Tolstoy that had begun to glimmer at the edges of my conscious mind. My wife and children were still asleep, and I couldn’t help but look at them fondly. How could I resist these sweet little boys who drove me nuts at times, as children must do, as it’s their job? Or a bright, affectionate wife who didn’t seem to mind my occasional flights of idiocy, offering a rueful smile at times, sometimes a deep laugh? This bounty felt undeserved and probably was. With a sense of gratitude, even amazement, I made my way downstairs into the country kitchen, where I brewed a strong cup of Irish Breakfast tea for myself before going into my study at the other end of the house.

As I often did before settling at the stained trestle table that still anchors my study, I turned on the radio to catch the headlines, tuning into the BBC on a shortwave radio that my old friend and mentor, Alastair Reid, had recently given to me as a gift for my thirty-eighth birthday. When the newscaster read the day’s top stories, I was stunned to hear that Jorge Luis Borges, the great Argentine writer “who blended fact and fiction in a peerless sequence of narratives that defied all boundaries and set off the Boom in Latin American literature,” had died in Geneva at the age of eighty-six. “He was a man of many stories,” the announcer said. “As a writer, he explored the most idiosyncratic spaces in the human experience, a lover of labyrinths and mirrors, a shapeshifting writer who could never be defined.”

Memories surfaced now. I had met Borges when I was a graduate student many years before, in Scotland, and traveled with him from St. Andrews to the Highlands and back. Our encounter lasted only a week or so, but it forced a shift in me, a change of perspective, hitting me at just the right time. And all I knew for sure was that my way of being in the world was never quite the same after Borges.

Standing at the window, I looked into the garden below at a bed of Oriental poppies, the blood-bright cheeks of the flowers turning toward me. Did they notice my stinging eyes? I thought so, and stepped away from the window. I’m not someone who cries easily, but I wept that day. Weeping as much for myself as for Borges, remembering the callow, overly serious, shy, and often terrified fellow I was when we met, trying to weigh this against the man I’d become, still wondering what on earth had happened to me in Scotland some fifteen years before.

—

In 1970, having just graduated from Lafayette College and moved (briefly, I hoped) back in with my parents in Scranton, Pennsylvania, I saw two choices: stay at home, where my mother would chop off my balls, or go to Vietnam, where they’d be blown off by a landmine. A third choice, less apparent at first but finally obvious, was to leave the United States altogether, getting as far away as possible. The place that called to me was a small town on the East Neuk of Fife, in Scotland.

St. Andrews had already provided me with a much-needed escape and given me a feeling of vocation, as I’d studied there for my junior year abroad. During a memorable year, I’d made friends easily, much to my surprise, mixing with Scottish and English students, befriending a handful of Continental students, too. The lectures I attended were often appealing—florid rhetorical performances of a kind unfamiliar to me—and I’d learned a good deal, especially from intense one-on-one tutorials with a range of eccentric but erudite teachers. (One of them held tutorials at his ramshackle flat, where his wife served us tea wearing a face mask as she was “sensitive to germs.”)

Most important, in Scotland I’d begun to write, recording my daily life in a journal, which I hoped (mentally cribbing a phrase from Robert Lowell) would shimmer with “the grace of accuracy.” No detail seemed too inconsequential to record, and I often filled pages with quotations from things I’d read or recorded snippets of conversation I’d overheard in tea shops or pubs. I also began to write my own poems. They were imitative and unmemorable, as one might expect, but this was a thrilling turn. I’d decided—for reasons based on no demonstrable talent or experience—to make a profession of writing.

I thought I knew quite a bit about literature, though I had a skim of learning, the lightest froth on a cup which was not even an especially big cup. Nonetheless, I’d begun to read with a sense of urgency. I gulped more than read books like Walden and Leaves of Grass, The Great Gatsby and Look Homeward, Angel. I scooped up Hesse, Woolf, Kerouac, Lawrence, McCullers, Nabokov, Beckett, and others. In libraries I leafed eagerly through the large, crisp pages of The New York Review of Books, drawn to provocative pieces by the likes of Gore Vidal, Joan Didion, Norman Mailer, and Susan Sontag. I attended readings by writers, some of them famous (Allen Ginsberg, James Dickey, Paul Goodman), and felt quite sure that literature would provide access to worlds far beyond Scranton.

I set my sights on graduate study in St. Andrews, though I knew it would be a battle to persuade my parents that this sort of move made sense. I was my mother’s first child, and she had been possessive from the first breath I drew. (My sister, Dorrie, was two years behind me, and her being a girl did not make it any easier with my mother, to put it mildly.) I was “backward,” my mother frequently said, which meant I was frightened by strangers, put off by everyone and everything. As a baby, I screamed whenever somebody unfamiliar stepped into the room. Only my mother could comfort me, and she encouraged this dependence. It wasn’t intentionally smothering, I suspect, but the results were the same. Needless to say, I would have great difficulty separating from her. Adulthood seemed a far, impossible kingdom.

My mother all but had a nervous breakdown when I left for Scotland the first time. “You’re going where?” she asked. “Scotland? Are you crazy? Nobody goes to Scotland!” The night before my first departure, in 1968, she hurled herself onto the bed in the hotel in New York in a state of emotional disarray. Her bitter wailing kept me awake in the adjacent room throughout the night, and she looked exhausted when she said goodbye to me at the docks the next morning, hardly uttering a word. I sailed away to Britain on a rickety Italian liner that she told me “was unstable and would probably sink.” It’s no wonder I wept quietly in my bunk on that low-rent ship on the eight-day journey from New York to Southampton. This was a kind of weaning for me, as I now see. I was shedding my old life as best I could. I could easily imagine my mother crying herself to sleep in Scranton, night after night, but I steeled myself, knowing that I had to go through whatever lay before me, no matter how painful.

My father was a genial worrywart, the son of Italian immigrants who spoke very little English and could offer their five sons few advantages beyond bowls of handmade linguini and homegrown vegetables. (My grandmother shot rabbits from her back porch and turned them into ragu.) Like many of his generation, children of the Great Depression, my father suffered from a pervasive cautiousness. The sidewalks of his mind were strewn with banana peels. He had been forced to leave high school well before graduating, but with a bit of luck and grit he made his way in the insurance business, selling local families policies that (I fear) he never quite understood himself. Every day he wore a suit with a starched white shirt and a colorful silk tie, holding his head high in Scranton. He polished his shoes before leaving the house with an exaggerated fervor. He had “made it.” And yet he continued to worry intensely about the future, especially my future.

So did I, and I was given a bottle of tranquilizers (old-fashioned barbiturates that would have stunned a horse) by our family doctor “to steady my nerves” before I set off to graduate school. “Don’t be so anxious,” Dr. Evans said to me. “All this nervousness isn’t good for you. If you stay up all night, you won’t get enough sleep. Just take the pills and stop worrying.”

So what exactly was I worried about? Pretty much everything, I think. The tidal wave of sex, drugs, and rock and roll on which my peers gleefully surfed felt to me more like a sea I might drown in. I was a virgin and afraid I might stay one forever. And more than anything, I was terrified of Vietnam, furious about a war fought over an illusion of freedom or world dominance or—more probably—something I couldn’t even imagine.

I had turned against the war during my freshman year in college, marching on Washington in 1967 and again in the spring of 1970. Like most college kids, I knew what I thought I knew: the war in Southeast Asia was immoral, stupid, and cruel. The antiwar writings of Howard Zinn, Noam Chomsky, and others became part of my permanent mental library. Making matters worse, my draft board had recently taken an interest in me, shifting my status after graduation from 2-S (student deferment) to 1-A (fit for active duty), even though I had drawn a reasonably high number in the lottery. I never quite metabolized this lucky draw and feared the worst, as my draft board in Lackawanna County was notorious, a prolific maw that gobbled up young men. Several of my friends from high school had been swept into the army, and one of them would soon end up in some godforsaken camp near the DMZ.

I still have nightmares about that morning at the armory in Scranton when, standing naked in line with dozens of others, I was prodded and poked by army doctors. “You call that a prick?” one sergeant yelled as I tried to hide my shriveled penis, which prompted barking laughter at my expense. One skinny guy I’d known from a tenth-grade physics class was there, and he passed out cold on the floor, foaming at the mouth, drawing his knees into a fetal position. “Send him first,” one of the recruiters said. “He’ll scare the shit out of them gooks.”

My mother was as determined as I was to keep me out of the action. Though I passed the army physical with flying colors, she was convinced I was unfit for service. “Think about your allergies. All night as a young boy you were coughing. That wheeze! You kept your poor sister awake all night. You still cough too much, especially in the spring, with the flowers, and it would keep the other soldiers awake in the barracks. They have enough to deal with in Vietnam without your health problems.” She had no end of schemes to keep me out of the military. As she wrote in one letter during my senior year in college, “Your Uncle Julie is well connected, and he knows a doctor who will certify that you can hardly breathe. Think how your chest feels when you exert yourself! And those feet of yours, without the arches. You couldn’t walk more than a few miles without sitting. What kind of army wants that? And by the way: Stop being so political. Why did you have to march on Washington, not once but twice? You’re not one of those hippies. You don’t understand as much about these things as you think you do.”

I spent many nights in the summer of 1970 arguing about the war with family and friends, especially Billy Giordano (as I will call him here), who had been a companion for some years, playing on my baseball team in junior high, joining me in pickup football after school in the fall, sometimes camping with me in the Poconos. He wasn’t a “smart kid,” as they say: not in any academic way. But I liked his freshness, his energy, and the kind of wild, subversive intelligence that doesn’t show up on exams. I made a point of seeking him out in the cafeteria at West Scranton High and finding ways to hang around him.

“This is our time,” he said only a day or so before he enlisted in the infantry that July, doing this “to avoid the draft”—a move that was perversely illogical and self-defeating. Unless, of course, what you really wanted was to go to Vietnam. “My dad was in the war against Hitler and Tojo,” he told me, “and he never regretted it. He thinks I should go.”

“Does he think I should go?”

“You should do whatever the fuck you want.”

When Billy came over to my house for a final visit before his induction, it was hard to look at him closely: the once innocently smooth face had become craggy, full of worry lines that summer. He had somehow broken a front tooth, which gave his smile a threatening appearance. He’d let his beard grow, unevenly; it showed itself in clumps of bristle on his cheeks and chin. His long and greasy hair brushed against his shoulders, and his neck needed shaving. He smelled of beer and cigarettes, had grown a little heavy, and spoke with a kind of pressured speech, as if History itself leaned over his shoulder and listened. Images of him at various stages in his adolescence floated in my head as I watched him talking. I saw him beside me in a canoe, fishing on some remote pond. Or dancing in the high school gym, making a fool of himself by leaping onto a table and bobbing his head obscenely to the lyrics of “Barbara Ann.” I always hoped to pitch on the baseball team in high school, and Billy was a gifted catcher who would let me throw lousy pitch after pitch into the dwindling pink-orange dusk at the sandlot field in Keyser Valley. When dark fell, we would sit together under a canopy of stars on the railroad tracks, talking about the nature and strangeness of life.

“I don’t know if there’s a God,” Billy had said to me once, “but there is pussy in the world. And I want to get as much of it as I can before I die. I do, yes, dear God.” I didn’t know whether or not to believe him, but I found his stories irresistible. And I loved Billy in part for the fearless way he lived his life. He took risks, and he encouraged me—without much success—to take risks. “If you don’t lay it on the line, Jay,” he would say, “what is the fucking point? Is there a fucking point?”

PUBLISHER:

Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group

ISBN-10:

198489949X

ISBN-13:

9781984899491

BINDING:

Paperback

BOOK DIMENSIONS:

Dimensions: 5.2500(W) x Dimensions: 7.9400(H) x Dimensions: 0.8500(D)