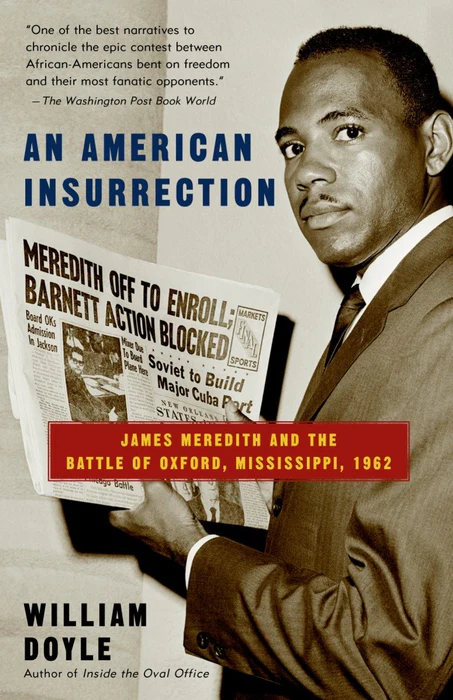

An American Insurrection

by Anchor

Sold out

Original price

$24.00

-

Original price

$24.00

Original price

$24.00

$24.00

-

$24.00

Current price

$24.00

In 1961, a black veteran named James Meredith applied for admission to the University of Mississippi — and launched a legal revolt against white supremacy in the most segregated state in America. Meredith’s challenge ultimately triggered what Time magazine called “the gravest conflict between federal and state authority since the Civil War,” a crisis that on September 30, 1962, exploded into a chaotic battle between thousands of white civilians and a small corps of federal marshals. To crush the insurrection, President John F. Kennedy ordered a lightning invasion of Mississippi by over 20,000 U.S. combat infantry, paratroopers, military police, and National Guard troops.

Based on years of intensive research, including over 500 interviews, JFK’s White House tapes, and 9,000 pages of FBI files, An American Insurrection is a minute-by-minute account of the crisis. William Doyle offers intimate portraits of the key players, from James Meredith to the segregationist Mississippi Governor Ross Barnett, to President John F. Kennedy and the federal marshals and soldiers who risked their lives to uphold the Constitution. The defeat of the segregationist uprising in Oxford was a turning point in the civil rights struggle, and An American Insurrection brings this largely forgotten event to life in all its drama, stunning detail, and historical importance.“One of the best narratives to chronicle the epic contest between African Americans bent on freedom and their most fanatic opponents.” –The Washington Post

“A compelling account of how the last battle of the Civil War came to be fought.... Precise and evocative.” –San Jose Mercury News

“Doyle has brought back into our historical consciousness a moment so shameful that it almost disappeared from memory.” –Houston Chronicle

“A dramatic tale.... Provide[s] fascinating detail of the inner workings of the White House and the weighing of political consequences for any decision.” –News & Observer

“A balanced narrative filled with fresh and important details.” –Wilson Quarterly

“Harrowing.... A riveting narrative.... [Doyle] describes the ebb and flow of the riot with more immediacy than any previous author has.” –The Times-Picayune

“An absorbing, important book.” –The Dallas Morning News

“A story of heroes, villains and cowards.... Doyle provides a captivating view of the motivations, both personal and political, of all the main players in the drama.” –Post & Courier (Charleston, SC)

“A fascinating contribution to civil rights history.” –Booklist

“Doyle has written a vivid portrait and riveting account....These insights render not only exciting, action-packed reading, but more importantly, a better understanding of what it means to be an American citizen.” –The Decatur Daily

“A riveting, true-life thriller.” –The Sacramento Bee

William Doyle’s previous book, Inside the Oval Office: The White House Tapes from FDR to Clinton (1999) was a New York Times Notable Book. In 1998 he won the Writers Guild of America Award for Best TV Documentary for the A&E special The Secret White House Tapes, which he co-wrote and co-produced. He lives in New York City. His email address is billdoyleusa@yahoo.com.CHAPTER ONE

Whom Shall I Fear?

We could have another Civil War on our hands.

--President Dwight D. Eisenhower, Cabinet meeting, March 1956

LITTLE ROCK, ARKANSAS, SEPTEMBER 8, 1957, 8:50 a.m.

A shy fifteen-year-old girl wearing bobby sox, ballet slippers, and a crisp black-and-white cotton dress stepped off a bus and walked toward Central High School, carrying a set of school books.

Elizabeth Eckford and nine other black students hoped to enter the all-white school today as part of a desegregation plan ordered by a federal judge. Because Eckford's family did not have a phone, she had missed the instructions to join the other students this morning, so she was walking toward the school completely alone.

Until today, Arkansas was making slow, peaceful progress toward integration. The state university was quietly desegregated in 1948, the state bus system had been integrated and black patrolmen were on the Little Rock police force. Several school districts were planning to accept black students this semester. In the wake of a lawsuit by the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People), the Little Rock school board had approved a plan to gradually desegregate Central High, and ten volunteer students were selected to go in.

Through her sunglasses Eckford could see the school up ahead, and she was amazed at how big it was. She was so nervous, she hadn't slept at all the night before, so to pass the time she had read her Bible. She dwelled on the opening passage of the Twenty-seventh Psalm: "The Lord is my light and my salvation; whom shall I fear? the Lord is the strength of my life; of whom shall I be afraid?"

As she neared the school, the girl became vaguely aware of a crowd of white people swarming around her. Somewhere a voice called out, "Here she comes, get ready!" People started shouting insults. "Then my knees started to shake all of a sudden," Eckford later explained privately to Little Rock NAACP leader Daisy Bates, "and I wondered whether I could make it to the center entrance a block away. It was the longest block I ever walked in my whole life."

Eckford could see uniformed soldiers ringing the entrance and letting white students into the school, and she assumed they were supposed to protect her. But when she approached the entrance, one soldier waved her away. When she tried to move past another soldier, he and his comrades lifted their bayonet-tipped M-1 rifles and surged toward her to block her path.

The soldiers were Arkansas National Guardsmen, and their commander in chief was Democratic governor Orval Eugene Faubus, who had ordered the troops to block the black students at gunpoint. Faubus was a hound dog-faced populist who was born in a plank cabin in a remote Ozark forest near a place called Greasy Creek, and grew up trapping skunks to help his family scrape out a living. Until today, he was considered something of a moderate on racial issues. But Faubus was up for reelection, and sensing a rising white backlash to integration, he decided to become its champion.

When she faced the solid wall of soldiers, Elizabeth Eckford wasn't sure what to do, so she retreated back across the street and into the white mob. Voices called out, "Lynch her! Lynch her!" and "Go home, you burr-head!" She scanned the mob for someone who might help her and spotted an old woman who seemed to have a kind face. The woman spat on her. A voice from the mob announced, "No nigger bitch is going to get in our school. Get out of here!"

The chanting mob swelled toward five hundred. Behind Eckford, someone said, "Push her!" Eckford later explained that she was afraid she would "bust out crying," and she "didn't want to in front of all that crowd." Ahead of her, news photographers snapped photos of a young white student named Hazel Bryan screaming at Eckford behind her back, a searing image that would soon be flashed around the world. "I looked down the block and saw a bench at the bus stop," recalled Eckford. "I thought, 'If only I can get there I will be safe.' I don't know why the bench seemed a safe place to me but I started walking toward it."

Eckford made it to the bus stop and sat down with her head bowed, tightly gripping her books as news cameras whirred and snapped. Someone in the crowd said, "Get a rope and drag her over to this tree." Benjamin Fine, an education reporter from the New York Times who had been scribbling notes in his steno pad, sat down next to Eckford, wrapped his arm around her shoulder, and whispered, "Don't let them see you cry."

A furious white woman named Grace Lorch fought her way through the mob, and screamed, "Leave this child alone! Why are you tormenting her? Six months from now, you will hang your heads in shame." Lorch tried to enter a drugstore to call a taxi for Eckford, but the door was slammed in her face.

"She's just a little girl," Lorch declared to the mob as she moved next to Eckford to defend her. "I'm just waiting for one of you to dare touch me! I'm just aching to punch somebody in the nose!"

Eventually a bus came, Mrs. Lorch helped Eckford up the stairs, and the bus pulled away. Eckford got off at the school for the blind, where her mother taught, and ran to her classroom. "Mother was standing at the window with her head bowed," Eckford recalled, "but she must have sensed I was there because she turned around. She looked as if she had been crying, and I wanted to tell her I was all right. But I couldn't speak. She put her arms around me and I cried."

Minutes after Eckford was turned away, her colleagues, who with her would soon become world famous as the "Little Rock Nine," were refused admission as well: Melba Pattillo, Gloria Ray, Carlotta Walls, Minnijean Brown, Thelma Mothershed, Ernest Green, Jefferson Thomas and Terrence Roberts. A tenth black student who was turned back, Jane Hill, chose to return to all-black Horace Mann High School.

Over the next two weeks, frantic negotiations resulted in a summit conference between President Dwight D. Eisenhower and Governor Faubus at Ike's vacation retreat in Newport, Rhode Island, during which the president thought he'd made a deal with Faubus to deploy Arkansas National Guardsmen to protect the black students as they entered Central High. But on September 23, when the Little Rock Nine tried again to enter the school, Faubus ordered the National Guard instead to abandon the premises.

Escorted by Little Rock police, the Nine briefly made it inside the school and started their classes. But outside the building, a furious mob of more than one thousand white civilians was surging against barricades, threatening to overwhelm the police trying to hold them in check. A white woman cried out hysterically to the police, "They've got the doors locked. They won't let the white kids out. My daughter's in there with those niggers. Oh, my God, oh God!" Policemen lashed out with their billy clubs, knocking down two men in the mob. "Come out!" adults yelled to the white students. "Don't stay in there with those niggers!"

A pack of fifty white men peeled off down a side street to chase a tall black journalist named Alex Wilson, civil rights reporter for Defender Publications, a national chain of black newspapers. A voice warned, "Run, nigger, run!" The mob caught up with Wilson and attacked him from behind with their fists. A brick slammed point-blank into the back of his head, and he tumbled to the ground like a mighty tree. Wilson raised himself to a kneeling position, was kicked and punched, but still he rose, grasping his hat in his hand. He brushed off his fedora, recreased it, and resumed walking.

"Strangely, the vision of Elizabeth Eckford flashed before me," Wilson recalled soon after the attack. "I decided not to run. If I were to be beaten, I'd take it walking if I could--not running." He told his wife, Emogene, "They would have had to kill me before I would have run." Another brick scored a direct hit on the back of Wilson's head, but he kept walking. "I looked into the tear-filled eyes of a white woman. Although there was sorrow in her eyes, I knew there would not be any help."

In a frantic effort to take Wilson down again, a crazed-looking, stocky white man in coveralls jumped clear up onto Wilson's back and wrapped his arm around his neck in a choke hold, but the ex-marine Wilson shook him off. "Don't kill him," a voice in the crowd cautioned the mob. Finally Wilson reached his car and escaped.

In front of Central High, a white policeman named Thomas Dunaway suddenly flung his billy club to the street, threw down his badge, and walked away from the barricade. The crowd cheered him, and a young man yelled, "He's the only white man on the force!" A hat was passed around the crowd, and it soon filled up with two hundred dollars in donations for the officer.

Inside Central High School, police and school officials gathered the nine black students. Word was relayed from the mob that they would not storm the building if one black pupil was turned over to them, presumably to be torn to pieces or hung from a tree. Instead, the Little Rock police chief evacuated the Nine out a side door into police cars that blasted away from the school.

At 12:14 p.m., police lieutenant Carl Jackson faced the mob and announced through a loudspeaker, "The Negroes have been withdrawn from the school." Someone in the crowd replied, "That's just a pack of lies!" Then another shouted, "We don't believe you!" A Mrs. Allen Thevenet stepped out from the mob and offered to verify the claim. After a full tour of the building, Mrs. Thevenet marched to the loudspeaker, and proclaimed, "We went through every room in the school and there was no niggers there."

White supremacists across the South rejoiced. Integration at Central High had been defeated in barely half a day.

The next day, September 24, President Eisenhower was back at the White House, and he was furious. He was supposed to still be on vacation. Instead, the old general was sitting at his desk in the Oval Office, dripping with rage over the treachery of Orval Faubus. "He double-crossed me," fumed the president.

On the wall of the elliptical presidential office were two small paintings, one of Union general and U.S. president Ulysses S. Grant, the other of Confederate general and Southern demigod Robert E. Lee. They captured the paradox at the heart of the America Eisenhower led. Nearly a century after the Civil War, as the nation asserted global moral leadership and reached out to explore the heavens, millions of black Americans were effectively not citizens of the country in which they were born.

That morning, the mayor of Little Rock had sent a desperate telegram to the president, who had been still savoring his relaxing vacation in Newport, Rhode Island. "The immediate need for federal troops is urgent," the mayor pleaded. "Situation is out of control and police cannot disperse the mob." Ike now feared a full-blown insurrection in the city.

The battle Eisenhower never wanted was hurtling toward him, and he was afraid it could tear the country apart. As his officials debated civil rights at a March 1956 Cabinet meeting, Eisenhower confessed, "I'm at sea on all this." He added, "Not enough people know how deep this emotion is in the South. Unless you've lived there you can't know. . . . We could have another Civil War on our hands."

On May 17, 1954, in its decision on Brown v. the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, the United States Supreme Court outlawed government-imposed segregation in public schools, but a year later the Court ruled that the order should be implemented not immediately, but "with all deliberate speed." This ambiguous phrase gave federal judges leeway to impose integration on varying timetables in different school districts, which delayed progress in some places well into the next decade.

Privately, Eisenhower disagreed with the Brown decision, and believed it could only be implemented slowly. "When emotions are deeply stirred," he wrote in July 1957 to his childhood friend Swede Hazlett, "logic and reason must operate gradually and with consideration for human feelings or we will have a resultant disaster rather than human advancement."

"School segregation itself," Ike pointed out, "was, according to the Supreme Court decision of 1896 [the Plessy v. Ferguson case], completely Constitutional until the reversal of that decision was accomplished in 1954. The decision of 1896 gave a cloak of legality to segregation in all its forms." People couldn't change overnight, Ike believed.

Dwight Eisenhower was a creature of forty years in the hermetically segregated U.S. military, and he personally had no quarrel with separation of the races. Although as president he quietly completed Harry S Truman's 1948 order desegregating of the armed forces and ordered the integration of public facilities in the nation's capital, not once in eight years in office did Ike publicly endorse the concept of integration. In that time he met with civil rights leaders on a grand total of one occasion--in a meeting that took less than an hour.

On the rare occasions he met with other black audiences, Eisenhower would sternly say, "Now, you people have to be patient." His attitude toward the black White House servants was "definitely not friendly" in the words of one of them, "the President hardly knew we were there." In private, he traded "nigger jokes" with his tycoon cronies.

Eisenhower appointed only one black person to his staff, and E. Frederic Morrow's experience as the first black White House official in history was pathetic. Promised a job during the 1952 campaign, Morrow showed up in Washington only to find the offer was withdrawn because White House employees threatened to boycott their jobs if he entered the building. The White House wouldn't return his calls.

Seventeen months later, an unemployed Morrow was offered temporary work in the Commerce Department. After he was finally moved to the White House two years later to work on miscellaneous "special projects," he was ignored by Eisenhower and humiliated by most everybody else. He couldn't find anyone to be his secretary. Women entered his office only in pairs to avoid talk of sexual misconduct. Morrow was not formally appointed and sworn in until 1959, and he spent much of his time feeling heartsick and ridiculous as he traveled the country defending Ike's indifferent civil rights stand to black audiences.

At the final White House Christmas party, Eisenhower pulled Morrow aside to say he had called all his friends but no one would hire a Negro. "Literally, out on my ear," Morrow reported. "I was the only member of the staff for whom the president could not find a job." It took him three years to find one.

Based on years of intensive research, including over 500 interviews, JFK’s White House tapes, and 9,000 pages of FBI files, An American Insurrection is a minute-by-minute account of the crisis. William Doyle offers intimate portraits of the key players, from James Meredith to the segregationist Mississippi Governor Ross Barnett, to President John F. Kennedy and the federal marshals and soldiers who risked their lives to uphold the Constitution. The defeat of the segregationist uprising in Oxford was a turning point in the civil rights struggle, and An American Insurrection brings this largely forgotten event to life in all its drama, stunning detail, and historical importance.“One of the best narratives to chronicle the epic contest between African Americans bent on freedom and their most fanatic opponents.” –The Washington Post

“A compelling account of how the last battle of the Civil War came to be fought.... Precise and evocative.” –San Jose Mercury News

“Doyle has brought back into our historical consciousness a moment so shameful that it almost disappeared from memory.” –Houston Chronicle

“A dramatic tale.... Provide[s] fascinating detail of the inner workings of the White House and the weighing of political consequences for any decision.” –News & Observer

“A balanced narrative filled with fresh and important details.” –Wilson Quarterly

“Harrowing.... A riveting narrative.... [Doyle] describes the ebb and flow of the riot with more immediacy than any previous author has.” –The Times-Picayune

“An absorbing, important book.” –The Dallas Morning News

“A story of heroes, villains and cowards.... Doyle provides a captivating view of the motivations, both personal and political, of all the main players in the drama.” –Post & Courier (Charleston, SC)

“A fascinating contribution to civil rights history.” –Booklist

“Doyle has written a vivid portrait and riveting account....These insights render not only exciting, action-packed reading, but more importantly, a better understanding of what it means to be an American citizen.” –The Decatur Daily

“A riveting, true-life thriller.” –The Sacramento Bee

William Doyle’s previous book, Inside the Oval Office: The White House Tapes from FDR to Clinton (1999) was a New York Times Notable Book. In 1998 he won the Writers Guild of America Award for Best TV Documentary for the A&E special The Secret White House Tapes, which he co-wrote and co-produced. He lives in New York City. His email address is billdoyleusa@yahoo.com.CHAPTER ONE

Whom Shall I Fear?

We could have another Civil War on our hands.

--President Dwight D. Eisenhower, Cabinet meeting, March 1956

LITTLE ROCK, ARKANSAS, SEPTEMBER 8, 1957, 8:50 a.m.

A shy fifteen-year-old girl wearing bobby sox, ballet slippers, and a crisp black-and-white cotton dress stepped off a bus and walked toward Central High School, carrying a set of school books.

Elizabeth Eckford and nine other black students hoped to enter the all-white school today as part of a desegregation plan ordered by a federal judge. Because Eckford's family did not have a phone, she had missed the instructions to join the other students this morning, so she was walking toward the school completely alone.

Until today, Arkansas was making slow, peaceful progress toward integration. The state university was quietly desegregated in 1948, the state bus system had been integrated and black patrolmen were on the Little Rock police force. Several school districts were planning to accept black students this semester. In the wake of a lawsuit by the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People), the Little Rock school board had approved a plan to gradually desegregate Central High, and ten volunteer students were selected to go in.

Through her sunglasses Eckford could see the school up ahead, and she was amazed at how big it was. She was so nervous, she hadn't slept at all the night before, so to pass the time she had read her Bible. She dwelled on the opening passage of the Twenty-seventh Psalm: "The Lord is my light and my salvation; whom shall I fear? the Lord is the strength of my life; of whom shall I be afraid?"

As she neared the school, the girl became vaguely aware of a crowd of white people swarming around her. Somewhere a voice called out, "Here she comes, get ready!" People started shouting insults. "Then my knees started to shake all of a sudden," Eckford later explained privately to Little Rock NAACP leader Daisy Bates, "and I wondered whether I could make it to the center entrance a block away. It was the longest block I ever walked in my whole life."

Eckford could see uniformed soldiers ringing the entrance and letting white students into the school, and she assumed they were supposed to protect her. But when she approached the entrance, one soldier waved her away. When she tried to move past another soldier, he and his comrades lifted their bayonet-tipped M-1 rifles and surged toward her to block her path.

The soldiers were Arkansas National Guardsmen, and their commander in chief was Democratic governor Orval Eugene Faubus, who had ordered the troops to block the black students at gunpoint. Faubus was a hound dog-faced populist who was born in a plank cabin in a remote Ozark forest near a place called Greasy Creek, and grew up trapping skunks to help his family scrape out a living. Until today, he was considered something of a moderate on racial issues. But Faubus was up for reelection, and sensing a rising white backlash to integration, he decided to become its champion.

When she faced the solid wall of soldiers, Elizabeth Eckford wasn't sure what to do, so she retreated back across the street and into the white mob. Voices called out, "Lynch her! Lynch her!" and "Go home, you burr-head!" She scanned the mob for someone who might help her and spotted an old woman who seemed to have a kind face. The woman spat on her. A voice from the mob announced, "No nigger bitch is going to get in our school. Get out of here!"

The chanting mob swelled toward five hundred. Behind Eckford, someone said, "Push her!" Eckford later explained that she was afraid she would "bust out crying," and she "didn't want to in front of all that crowd." Ahead of her, news photographers snapped photos of a young white student named Hazel Bryan screaming at Eckford behind her back, a searing image that would soon be flashed around the world. "I looked down the block and saw a bench at the bus stop," recalled Eckford. "I thought, 'If only I can get there I will be safe.' I don't know why the bench seemed a safe place to me but I started walking toward it."

Eckford made it to the bus stop and sat down with her head bowed, tightly gripping her books as news cameras whirred and snapped. Someone in the crowd said, "Get a rope and drag her over to this tree." Benjamin Fine, an education reporter from the New York Times who had been scribbling notes in his steno pad, sat down next to Eckford, wrapped his arm around her shoulder, and whispered, "Don't let them see you cry."

A furious white woman named Grace Lorch fought her way through the mob, and screamed, "Leave this child alone! Why are you tormenting her? Six months from now, you will hang your heads in shame." Lorch tried to enter a drugstore to call a taxi for Eckford, but the door was slammed in her face.

"She's just a little girl," Lorch declared to the mob as she moved next to Eckford to defend her. "I'm just waiting for one of you to dare touch me! I'm just aching to punch somebody in the nose!"

Eventually a bus came, Mrs. Lorch helped Eckford up the stairs, and the bus pulled away. Eckford got off at the school for the blind, where her mother taught, and ran to her classroom. "Mother was standing at the window with her head bowed," Eckford recalled, "but she must have sensed I was there because she turned around. She looked as if she had been crying, and I wanted to tell her I was all right. But I couldn't speak. She put her arms around me and I cried."

Minutes after Eckford was turned away, her colleagues, who with her would soon become world famous as the "Little Rock Nine," were refused admission as well: Melba Pattillo, Gloria Ray, Carlotta Walls, Minnijean Brown, Thelma Mothershed, Ernest Green, Jefferson Thomas and Terrence Roberts. A tenth black student who was turned back, Jane Hill, chose to return to all-black Horace Mann High School.

Over the next two weeks, frantic negotiations resulted in a summit conference between President Dwight D. Eisenhower and Governor Faubus at Ike's vacation retreat in Newport, Rhode Island, during which the president thought he'd made a deal with Faubus to deploy Arkansas National Guardsmen to protect the black students as they entered Central High. But on September 23, when the Little Rock Nine tried again to enter the school, Faubus ordered the National Guard instead to abandon the premises.

Escorted by Little Rock police, the Nine briefly made it inside the school and started their classes. But outside the building, a furious mob of more than one thousand white civilians was surging against barricades, threatening to overwhelm the police trying to hold them in check. A white woman cried out hysterically to the police, "They've got the doors locked. They won't let the white kids out. My daughter's in there with those niggers. Oh, my God, oh God!" Policemen lashed out with their billy clubs, knocking down two men in the mob. "Come out!" adults yelled to the white students. "Don't stay in there with those niggers!"

A pack of fifty white men peeled off down a side street to chase a tall black journalist named Alex Wilson, civil rights reporter for Defender Publications, a national chain of black newspapers. A voice warned, "Run, nigger, run!" The mob caught up with Wilson and attacked him from behind with their fists. A brick slammed point-blank into the back of his head, and he tumbled to the ground like a mighty tree. Wilson raised himself to a kneeling position, was kicked and punched, but still he rose, grasping his hat in his hand. He brushed off his fedora, recreased it, and resumed walking.

"Strangely, the vision of Elizabeth Eckford flashed before me," Wilson recalled soon after the attack. "I decided not to run. If I were to be beaten, I'd take it walking if I could--not running." He told his wife, Emogene, "They would have had to kill me before I would have run." Another brick scored a direct hit on the back of Wilson's head, but he kept walking. "I looked into the tear-filled eyes of a white woman. Although there was sorrow in her eyes, I knew there would not be any help."

In a frantic effort to take Wilson down again, a crazed-looking, stocky white man in coveralls jumped clear up onto Wilson's back and wrapped his arm around his neck in a choke hold, but the ex-marine Wilson shook him off. "Don't kill him," a voice in the crowd cautioned the mob. Finally Wilson reached his car and escaped.

In front of Central High, a white policeman named Thomas Dunaway suddenly flung his billy club to the street, threw down his badge, and walked away from the barricade. The crowd cheered him, and a young man yelled, "He's the only white man on the force!" A hat was passed around the crowd, and it soon filled up with two hundred dollars in donations for the officer.

Inside Central High School, police and school officials gathered the nine black students. Word was relayed from the mob that they would not storm the building if one black pupil was turned over to them, presumably to be torn to pieces or hung from a tree. Instead, the Little Rock police chief evacuated the Nine out a side door into police cars that blasted away from the school.

At 12:14 p.m., police lieutenant Carl Jackson faced the mob and announced through a loudspeaker, "The Negroes have been withdrawn from the school." Someone in the crowd replied, "That's just a pack of lies!" Then another shouted, "We don't believe you!" A Mrs. Allen Thevenet stepped out from the mob and offered to verify the claim. After a full tour of the building, Mrs. Thevenet marched to the loudspeaker, and proclaimed, "We went through every room in the school and there was no niggers there."

White supremacists across the South rejoiced. Integration at Central High had been defeated in barely half a day.

The next day, September 24, President Eisenhower was back at the White House, and he was furious. He was supposed to still be on vacation. Instead, the old general was sitting at his desk in the Oval Office, dripping with rage over the treachery of Orval Faubus. "He double-crossed me," fumed the president.

On the wall of the elliptical presidential office were two small paintings, one of Union general and U.S. president Ulysses S. Grant, the other of Confederate general and Southern demigod Robert E. Lee. They captured the paradox at the heart of the America Eisenhower led. Nearly a century after the Civil War, as the nation asserted global moral leadership and reached out to explore the heavens, millions of black Americans were effectively not citizens of the country in which they were born.

That morning, the mayor of Little Rock had sent a desperate telegram to the president, who had been still savoring his relaxing vacation in Newport, Rhode Island. "The immediate need for federal troops is urgent," the mayor pleaded. "Situation is out of control and police cannot disperse the mob." Ike now feared a full-blown insurrection in the city.

The battle Eisenhower never wanted was hurtling toward him, and he was afraid it could tear the country apart. As his officials debated civil rights at a March 1956 Cabinet meeting, Eisenhower confessed, "I'm at sea on all this." He added, "Not enough people know how deep this emotion is in the South. Unless you've lived there you can't know. . . . We could have another Civil War on our hands."

On May 17, 1954, in its decision on Brown v. the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, the United States Supreme Court outlawed government-imposed segregation in public schools, but a year later the Court ruled that the order should be implemented not immediately, but "with all deliberate speed." This ambiguous phrase gave federal judges leeway to impose integration on varying timetables in different school districts, which delayed progress in some places well into the next decade.

Privately, Eisenhower disagreed with the Brown decision, and believed it could only be implemented slowly. "When emotions are deeply stirred," he wrote in July 1957 to his childhood friend Swede Hazlett, "logic and reason must operate gradually and with consideration for human feelings or we will have a resultant disaster rather than human advancement."

"School segregation itself," Ike pointed out, "was, according to the Supreme Court decision of 1896 [the Plessy v. Ferguson case], completely Constitutional until the reversal of that decision was accomplished in 1954. The decision of 1896 gave a cloak of legality to segregation in all its forms." People couldn't change overnight, Ike believed.

Dwight Eisenhower was a creature of forty years in the hermetically segregated U.S. military, and he personally had no quarrel with separation of the races. Although as president he quietly completed Harry S Truman's 1948 order desegregating of the armed forces and ordered the integration of public facilities in the nation's capital, not once in eight years in office did Ike publicly endorse the concept of integration. In that time he met with civil rights leaders on a grand total of one occasion--in a meeting that took less than an hour.

On the rare occasions he met with other black audiences, Eisenhower would sternly say, "Now, you people have to be patient." His attitude toward the black White House servants was "definitely not friendly" in the words of one of them, "the President hardly knew we were there." In private, he traded "nigger jokes" with his tycoon cronies.

Eisenhower appointed only one black person to his staff, and E. Frederic Morrow's experience as the first black White House official in history was pathetic. Promised a job during the 1952 campaign, Morrow showed up in Washington only to find the offer was withdrawn because White House employees threatened to boycott their jobs if he entered the building. The White House wouldn't return his calls.

Seventeen months later, an unemployed Morrow was offered temporary work in the Commerce Department. After he was finally moved to the White House two years later to work on miscellaneous "special projects," he was ignored by Eisenhower and humiliated by most everybody else. He couldn't find anyone to be his secretary. Women entered his office only in pairs to avoid talk of sexual misconduct. Morrow was not formally appointed and sworn in until 1959, and he spent much of his time feeling heartsick and ridiculous as he traveled the country defending Ike's indifferent civil rights stand to black audiences.

At the final White House Christmas party, Eisenhower pulled Morrow aside to say he had called all his friends but no one would hire a Negro. "Literally, out on my ear," Morrow reported. "I was the only member of the staff for whom the president could not find a job." It took him three years to find one.

PUBLISHER:

Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group

ISBN-10:

0385499701

ISBN-13:

9780385499705

BINDING:

Paperback

BOOK DIMENSIONS:

Dimensions: 5.1900(W) x Dimensions: 7.9600(H) x Dimensions: 0.8800(D)