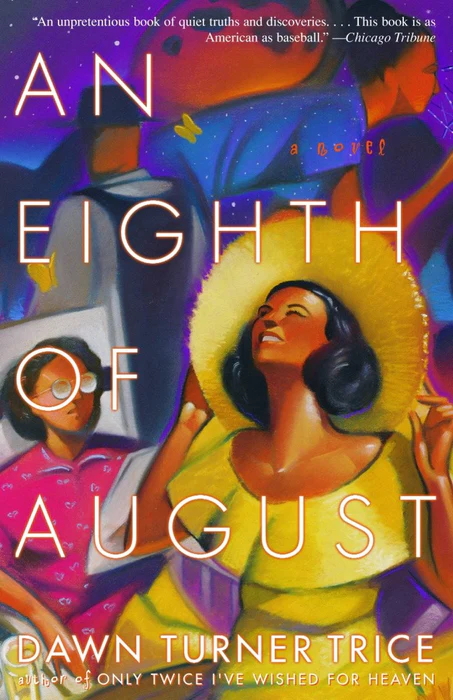

An Eighth of August

by Anchor

Sold out

Original price

$13.00

-

Original price

$13.00

Original price

$13.00

$13.00

-

$13.00

Current price

$13.00

From the author of the highly acclaimed Only Twice I’ve Wished for Heaven, a new novel about the strong ties and haunting memories that bind family and friends in a small town.

Narrated by a chorus of voices, An Eighth of August tells the story of a Midwestern community that celebrates the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation year after year. Celebrants from come near and far to pay tribute to the rich heritage of the former slaves who settled the Illinois town. But along with the festivities come painful memories and long-buried resentments, and while this year’s celebration is no different, it will offer up its own particular brand of freedom to one extended family and the wonderfully eccentric white woman whose life becomes entwined with their own. Wavering between the devastating and the uplifting, An Eighth of August is ultimately an enduring and exuberant novel.“An unpretentious book of quiet truths and discoveries. . . . This book is as American as baseball.” –Chicago Tribune

“Absolutely glistens with a unique writing style.” –Fort Worth Star-Telegram

“A beautifully layered tale about an extended family and its small town dealings” –Black Issues Book Review Dawn Turner Trice is the author of Only Twice I’ve Wished for Heaven. She writes for the Chicago Tribune and NPR’s Morning Edition. She lives outside Chicago.J. Herbert Gray

The 1986 Halley's Landing Emancipation Festival

Sunday, August 3, 1986

From the start . . .

From the very start, them women on the Mothers Board say they saw her coming up the shoulder of the road, half dressed and walking scatter-legged 'long the side that hugs the river.

Them no-seeing women on Greater Faith's Mothers Board say they knowed it was her even when they was looking straight ahead up toward the pulpit at young Delaware Matthews, the assistant pastor, and she was merely caught up in their side glance. Them women say they knowed right off who it was just as soon as they saw all that pretty yellow coming toward the church. Yellow set 'gainst green countryside and the clear blue sky. 'Gainst newly laid black asphalt with a fresh white seam painted straight up the middle, so ain't no mistaking which side for heading east and which for heading west. One woman say yellow that pretty used to belong only to the sunflowers in the patch on the other side of town. But that was before Sis moved to Halley. Folk liked to intuit that women with skin that dark couldn't, or shouldn't, hold claim to such a vibrant color. But Flossie Jo never cared 'bout such particulars. Wore it without shame or sorrow, like she owned it and the sun, too; walked--when she wasn't walking scatter-legged--like she had wings and could show it off finer than any bird or butterfly of the same hue.

Them women on the Mothers Board say they was standing right here in this front pew, looking out this window, when they saw her. Never mind that the day was hazy and you could hardly see for the heat waves making everything ripple and blur. Heat beating down from the sun and rising up from that black asphalt, meeting in the middle in a steamy crease. Them women say they saw her, never mind them black fringes on the window's awning. Them fringes always hang long like scrappy thin pickaninny braids and nearly block the view. Still, them women say them fringes wasn't making no difference that morning. Neither was their wide and cocked, colorful Sunday hats or their rheumatized joints or their bad feet, which taken together made them stand stooped over and made seeing straight even more of a chore. They say when they saw Sis coming toward the church, everything sorta moved out the way; sorta opened up or eased up to let her through. They remember the exact moment she deboarded the bus under the last of all them fine houses on the hill. They remember 'cause them propane cannons sounded, nearly jarring the deafness out of them. They even recall when she crossed the Jefferson bridge, officially entering the downtown, and not long after that, stepped under the

WELCOME TO THE 1973 HALLEY'S LANDING EMANCIPATION FESTIVAL

banner that stretched between the cornices of the old glass company and the taxi place.

Them five women say by the time she made it halfway to the church and was hovering 'bout the Mercury Filling Station, they had done finished Communion--had gulped down double portions of that potent elderberry wine--and was up clapping and singing, swaying, though they couldn't recall the song. They did remember sorta that the choir was standing, too, and so was the young people up above in the loft area, and so was young Delaware and Pastor hisself--who, standing next to Delaware, always lost some of his handsomeness, what with that good-sized hole eating into his Afro. You noticed Pastor's hole only 'cause Delaware had a head full of that curly hair. And with Pastor's head and Delaware's head bowed over the empty Communion vials, Pastor's hole gaped wide open and shined, too, on account of the sweltering heat. So many people had done arrived for the goings-on that every seat in the sanctuary was filled to overflowing and everything running water: the walls, the floors, the pews, the people, and naturally, Pastor's head.

At one point, them women say, the big fat organist grabbed their attention 'cause he jumped up from his bench and screamed hallelujah. The music fell off as he hot-footed it down the center aisle toward the rear of the sanctuary. He turned the corner, smacking into the last row of pews--pews that don't offer much in the way of comforts for sitting, let alone for smacking into them--and rolled back up toward the pulpit 'long the outside aisle by the windows.

Them women was certain he ain't seen nothing outside that window, or 'round them fringes, or through the haze, what with his eyes squeezed shut the way they was, which explained why he smacked into them pews, bruising and welting up his stumpy legs. Windows may as well have been pushed down, showing off the stained glass, rather than propped open, beckoning a breeze. Especially since there was no breeze to speak of and the onliest thing coming in through those windows was a few of them forehead-kissing horseflies and, every now and then, a whiff of that good ol' barbecue pit smoke from the fairgrounds behind the church. Air was so thick and smelling so good that every time Pastor shook his tambourine and said "Somebody say Amen," you said "Amen" and tasted hot tangy sauce and soft white bread.

Narrated by a chorus of voices, An Eighth of August tells the story of a Midwestern community that celebrates the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation year after year. Celebrants from come near and far to pay tribute to the rich heritage of the former slaves who settled the Illinois town. But along with the festivities come painful memories and long-buried resentments, and while this year’s celebration is no different, it will offer up its own particular brand of freedom to one extended family and the wonderfully eccentric white woman whose life becomes entwined with their own. Wavering between the devastating and the uplifting, An Eighth of August is ultimately an enduring and exuberant novel.“An unpretentious book of quiet truths and discoveries. . . . This book is as American as baseball.” –Chicago Tribune

“Absolutely glistens with a unique writing style.” –Fort Worth Star-Telegram

“A beautifully layered tale about an extended family and its small town dealings” –Black Issues Book Review Dawn Turner Trice is the author of Only Twice I’ve Wished for Heaven. She writes for the Chicago Tribune and NPR’s Morning Edition. She lives outside Chicago.J. Herbert Gray

The 1986 Halley's Landing Emancipation Festival

Sunday, August 3, 1986

From the start . . .

From the very start, them women on the Mothers Board say they saw her coming up the shoulder of the road, half dressed and walking scatter-legged 'long the side that hugs the river.

Them no-seeing women on Greater Faith's Mothers Board say they knowed it was her even when they was looking straight ahead up toward the pulpit at young Delaware Matthews, the assistant pastor, and she was merely caught up in their side glance. Them women say they knowed right off who it was just as soon as they saw all that pretty yellow coming toward the church. Yellow set 'gainst green countryside and the clear blue sky. 'Gainst newly laid black asphalt with a fresh white seam painted straight up the middle, so ain't no mistaking which side for heading east and which for heading west. One woman say yellow that pretty used to belong only to the sunflowers in the patch on the other side of town. But that was before Sis moved to Halley. Folk liked to intuit that women with skin that dark couldn't, or shouldn't, hold claim to such a vibrant color. But Flossie Jo never cared 'bout such particulars. Wore it without shame or sorrow, like she owned it and the sun, too; walked--when she wasn't walking scatter-legged--like she had wings and could show it off finer than any bird or butterfly of the same hue.

Them women on the Mothers Board say they was standing right here in this front pew, looking out this window, when they saw her. Never mind that the day was hazy and you could hardly see for the heat waves making everything ripple and blur. Heat beating down from the sun and rising up from that black asphalt, meeting in the middle in a steamy crease. Them women say they saw her, never mind them black fringes on the window's awning. Them fringes always hang long like scrappy thin pickaninny braids and nearly block the view. Still, them women say them fringes wasn't making no difference that morning. Neither was their wide and cocked, colorful Sunday hats or their rheumatized joints or their bad feet, which taken together made them stand stooped over and made seeing straight even more of a chore. They say when they saw Sis coming toward the church, everything sorta moved out the way; sorta opened up or eased up to let her through. They remember the exact moment she deboarded the bus under the last of all them fine houses on the hill. They remember 'cause them propane cannons sounded, nearly jarring the deafness out of them. They even recall when she crossed the Jefferson bridge, officially entering the downtown, and not long after that, stepped under the

WELCOME TO THE 1973 HALLEY'S LANDING EMANCIPATION FESTIVAL

banner that stretched between the cornices of the old glass company and the taxi place.

Them five women say by the time she made it halfway to the church and was hovering 'bout the Mercury Filling Station, they had done finished Communion--had gulped down double portions of that potent elderberry wine--and was up clapping and singing, swaying, though they couldn't recall the song. They did remember sorta that the choir was standing, too, and so was the young people up above in the loft area, and so was young Delaware and Pastor hisself--who, standing next to Delaware, always lost some of his handsomeness, what with that good-sized hole eating into his Afro. You noticed Pastor's hole only 'cause Delaware had a head full of that curly hair. And with Pastor's head and Delaware's head bowed over the empty Communion vials, Pastor's hole gaped wide open and shined, too, on account of the sweltering heat. So many people had done arrived for the goings-on that every seat in the sanctuary was filled to overflowing and everything running water: the walls, the floors, the pews, the people, and naturally, Pastor's head.

At one point, them women say, the big fat organist grabbed their attention 'cause he jumped up from his bench and screamed hallelujah. The music fell off as he hot-footed it down the center aisle toward the rear of the sanctuary. He turned the corner, smacking into the last row of pews--pews that don't offer much in the way of comforts for sitting, let alone for smacking into them--and rolled back up toward the pulpit 'long the outside aisle by the windows.

Them women was certain he ain't seen nothing outside that window, or 'round them fringes, or through the haze, what with his eyes squeezed shut the way they was, which explained why he smacked into them pews, bruising and welting up his stumpy legs. Windows may as well have been pushed down, showing off the stained glass, rather than propped open, beckoning a breeze. Especially since there was no breeze to speak of and the onliest thing coming in through those windows was a few of them forehead-kissing horseflies and, every now and then, a whiff of that good ol' barbecue pit smoke from the fairgrounds behind the church. Air was so thick and smelling so good that every time Pastor shook his tambourine and said "Somebody say Amen," you said "Amen" and tasted hot tangy sauce and soft white bread.

PUBLISHER:

Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group

ISBN-10:

0385721471

ISBN-13:

9780385721479

BINDING:

Paperback

BOOK DIMENSIONS:

Dimensions: 5.1800(W) x Dimensions: 7.9900(H) x Dimensions: 0.7000(D)